On January 31, 2019, the Department of Health and Human Services’s (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) issued a proposed rule it believes “may curb list price increases, reduce financial burdens on beneficiaries, lower or increase Federal expenditures, improve transparency, and reduce the likelihood that rebates would serve to inappropriately induce business payable by Medicare Part D and Medicaid MCOs [managed care organizations].”1

What is a rebate?

In its simplest form, a rebate is a seller’s return of some of the purchase price to the buyer. Rebates are paid to wholesalers or retailers by manufacturers in a wide array of industries to improve the market share of one or more of the manufacturer’s products. For prescription drugs, rebates are mostly used for brand-name prescription drugs in competitive therapeutic classes where there are reasonably interchangeable prescription drugs (rebates are rarely offered for generics).

HHS OIG proposes changes to the Anti-Kickback Statute safe harbors to ban rebate arrangements it believes are harmful, while protecting discount and service arrangements it believes are beneficial. Although the proposal applies to both Medicare Advantage and Managed Medicaid, in this paper we focus on Part D stakeholders. Some Medicaid MCOs and state Medicaid programs could see impacts based on their specific circumstances. In a subsequent paper, we discuss financial scenarios for these Part D program stakeholders.

Prescription drug prices, rebates, and the Anti-Kickback Statute in Medicare

Since 2010, existing pharmaceutical drug prices have risen more rapidly than inflation.2 Research by HHS found that drug price increases may reflect significant distortions in the distribution chain.3 More recently, the Trump administration has focused on distribution chain issues in its attempts to lower drug prices and reduce patient out-of-pocket (OOP) costs.

The Anti-Kickback Statute and Safe Harbors

Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS): Provides for criminal penalties for whoever knowingly and willfully offers, pays, solicits, or receives remuneration to induce or reward the referral of business reimbursable under any of the federal healthcare programs.

Section 1128B(b) of the Social Security Act, originally adopted in 1972 and as amended in 1977

AKS safe harbors: In 1987, Congress enacted the establishment of safe harbor provisions that protect relatively innocuous commercial payment arrangements from AKS sanctions, even though they may be capable of inducing referrals of business for which payment may be made under a federal healthcare program. The discount safe harbor was adopted in 1991 to align with the law’s intent to encourage price competition that benefits the Medicare and Medicaid programs.4 OIG defined discount to include protection for rebate checks and then later defined “rebate” to include “any discount the terms of which are fixed at the time of the sale of the good or service and disclosed to the buyer, but which is not received at the time of the sale of the good or service.”5,6 In 2002, the discount safe harbor was expanded to cover discounts for items or services for which payment may be made, in whole or in part, under Medicare, Medicaid, or other federal healthcare programs.7

The broad Anti-Kickback Statute prohibits payments to induce or reward the referral of business reimbursable under any of the federal healthcare programs. Since the inclusion of remuneration under the AKS in 1977, HHS OIG has established various safe harbors to protect what it deems certain non-abusive business arrangements, while encouraging beneficial or innocuous arrangements.8 The discount safe harbor was adopted prior to the enactment of the Medicare prescription drug benefit and prior to the adoption of comprehensive regulations governing Medicaid managed care delivery systems.

The discount safe harbor currently allows the payment of rebates by manufacturers to payers, which are often offered in exchange for favorable formulary status. In most cases, Current Manufacturer Rebates—rebates offered by prescription drug manufacturers to pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and health plans—are expressed as a percentage of list price, so as list prices increase, the dollar value of rebates also increases. Additionally, price protection rebates, which are a form of manufacturer rebates designed to limit the impact of list price increases on payers, have also become more common and represent an increasingly large share of Current Manufacturer Rebates.

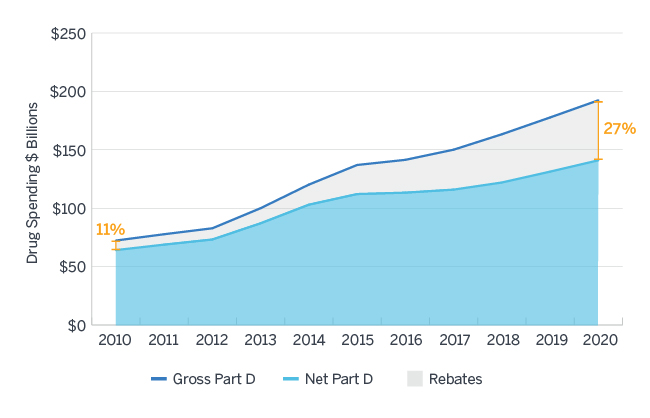

Between 2010 and 2015, the amount of all forms of rebates received by Medicare Part D sponsors and their PBMs increased nearly 24% annually, much faster than the overall growth in gross drug costs in that same time period. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Office of the Actuary projects rebates of all forms to comprise nearly 27% of Medicare Part D gross drug costs in 2020, up from 11% in 2010, as displayed in Figure 1.9 A Milliman analysis commissioned by HHS estimates these rebates would be worth $43.4 billion in 2020 under current regulation.10 Current Manufacturer Rebates, which comprise the largest share of all price concessions received, have accounted for much of this growth.

Figure 1: Gross and Net Part D Spending 2010 - 2020

Source: Milliman analysis of Medicare Trustees Report, National Health Expenditure Data, and Medicare Part D Spending Dashboard Data11,12,13

Proposed changes to AKS safe harbors

|

Remove safe harbor protection for prescription drug manufacturer rebates to plan sponsors under Medicare Part D and Medicaid MCOs, as well as PBMs under contract with them. The proposed effective date is January 1, 2020. The change excludes:

|

|

Add safe harbor protection for certain price reductions offered by prescription drug manufacturers to Part D plans and Medicaid MCOs that are reflected at the point of sale (POS) to the beneficiary. The proposed effective date is 60 days after publication of the final rule. Protected discounts offered by drug manufacturers at the POS must be:

|

|

Add safe harbor protection for fixed fees that prescription drug manufacturers pay to PBMs for services rendered to the manufacturers that meet specified criteria. The proposed effective date is January 1, 2020. Protected fee arrangements must include:

|

The proposed rule

The explicit goals of the proposed rule released January 31, 2019, are to lower out-of-pocket costs for consumers and reduce government drug spending in federal healthcare programs.14 The proposed rule was published in the Federal Register on February 6 and is available online. The public comment period closes at 5 PM Eastern Standard Time on April 8, 2019.

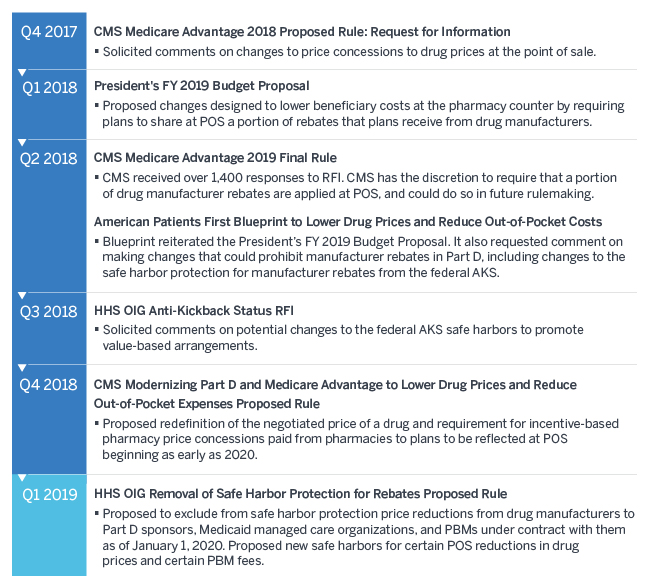

Advocates of the proposed rule argue that the existing rebate-based system harms beneficiaries because Current Manufacturer Rebates do not directly flow through to the consumers purchasing the prescription drugs. These stakeholders assert that prescription drug manufacturer rebates ultimately drive up list prices (and therefore Medicare and Medicaid spending), which is contrary to the purpose of the discount safe harbor. Finally, they claim that Current Manufacturer Rebates create a lack of price transparency for some stakeholders. Figure 2 summarizes major federal government activities over the past 15 months that signal potential policy changes to alter the dynamics of rebates in Medicare Part D. These activities tend to support the proposed rule released January 31, 2019.

Figure 2: Sequence of Federal Government Activities on Price Concessions 15,16,17,18,19,20,21

*Designated by calendar year quarter

Current rebates from prescription drug manufacturers

For Medicare Part D plans, prescription drug rebates have historically been paid by prescription drug manufacturers to the plans, which then share a portion of the rebate with the federal government (Current Manufacturer Rebates).22 Other types of rebates impact Medicare Part D, most notably rebates paid by retail pharmacies known as pharmacy direct and indirect remuneration (DIR). CMS addresses pharmacy DIR in a separate proposed rule published in the November 30, 2018, Federal Register.23 The proposals on pharmacy DIR have not been finalized as of the time this paper was written.

Rebate contract terms are considered trade secrets and vary widely among individual prescription drugs, prescription drug manufacturers, and Medicare Part D plans. This secrecy makes it difficult for the public to compare the net costs of particular prescription drugs, but purchasers (e.g., PBMs) can compare competing offers from prescription drug manufacturers. In 2016, the average rebate was about 22% for Medicare Part D plans. Some brand products had no rebates and others had rebates exceeding 50% of the list price.24

Rebates (including Current Manufacturer Rebates and pharmacy DIR) are shared between Part D plans (or the plan’s PBM, which passes some or all rebates to the plan) and the federal government. They are not generally shared directly with beneficiaries at the pharmacy counter and, therefore, do not impact the cost-sharing amounts patients pay for prescription drugs. Plans tend to use rebates to reduce premiums for the plans they offer. The federal government share of rebates equals the portion of government liability for prescription drug spending in the catastrophic benefit phase, which has been increasing steadily over time as prescription drug prices increase and new high-cost therapies become available. According to analysis by Milliman, the government share of rebates likely currently exceeds 35%.

The POS Manufacturer Rebate alternative

In contrast to the manner in which Current Manufacturer Rebates are retained by the health plans, reflecting manufacturer rebates at the POS (POS Manufacturer Rebates) would directly impact patient cost-sharing amounts. POS Manufacturer Rebates function much like a discount applied at the POS, directly reducing the patient’s OOP expense by applying the rebate to the prescription drug price from which the patient’s coinsurance is calculated. The 2019 CVS Allure Part D plan is the only Part D plan known to provide POS Manufacturer Rebates.25

See Section 1 of Figure 3 for an example of Current Manufacturer versus POS Manufacturer Rebates in the initial coverage phase. While the application of rebates to OOP costs reduces patients’ liability, it also delays patients moving through the coverage phases, which would impact all stakeholders. In particular, the application of rebates at the POS would impact Part D plans because these plans use rebates to reduce (or even eliminate) plan liability—particularly once patients enter the catastrophic coverage phase. Section 2 of Figure 3 shows an example of Current Manufacturer versus POS Manufacturer Rebates in the catastrophic coverage phase.

Figure 3: Current Manufacturer versus POS Manufacturer Rebates

| Stakeholder | Transaction | Current manufacturer rebates | POS manufacturer rebates | Notes |

| Manufacturer list price | $1000 | $1000 | (A) | |

| Manufacturer rebate | $300 | $300 | (B) = (A) * 30% | |

| Portion retained by Part D Plan* | $195 | $0 | (C) = (B) * 65% (Plan keeps 65% of rebate) | |

| Portion retained by federal government** | $105 | $0 | (D) = (B) * 35% (Federal government keeps 35% of rebate) | |

| Portion passed to POS (shared with patient) | $0 | $300 | (E) | |

| Pharmaceutical manufacturer | Final POS price | $1000 | $700 | (F) = (A) - (E) |

| Net revenue | $700 | $700 | (G) = (A) - (B) | |

| Section 1: Initial coverage phase (75% plan liability / 25% member cost sharing) with no behavior change | ||||

| Patient | Coinsurance (25%) | $250 | $175 | (H) = (F) * 25% |

| Health plan | Net plan cost | $555 | $525 | (I) = (F) - (C) - (H) |

| Section 2: Catastrophic coverage phase (80% Federal Reinsurance / 15% plan liability / 5% member cost sharing) with no behavior change | ||||

| Federal government | Reinsurance (80%) | $800 | $560 | (J) = (F) * 80% |

| Patient | Coinsurance (5%) | $50 | $35 | (K) = (F) * 5% |

| Health plan | Net plan cost | ($45)*** | $105 | (L) = (F) - (C) - (J) - (K) |

*PBMs may receive a portion of the rebates under Medicare Part D; however, many larger plans keep all of the rebates. In addition, some PBMs are owned by health insurers while other prescription drug plans are owned by PBMs.26

**Government retains 35% of rebates in our illustration. Actual percentage will vary widely based on plan-specific claim experience, plan design, and enrolled population.

***Negative Net Plan Cost indicates the plan receives more in rebates than its liability; this dynamic can occur because the federal government share of rebates is calculated at an aggregate level and not on an individual claim.

Primarily Medicare Part D, less impact to Medicaid and commercial

Currently, the commercial market has the greatest volume of patients and, therefore, the largest volume of prescription drug spending.27 The current HHS OIG proposal would only apply to Medicare Part D plans and certain Medicaid MCOs; it would not directly require changes to rebates in the commercial market. Medicaid MCOs would generally have similar rebate economics whether rebates are passed to the POS or not, because Medicaid beneficiaries tend to have very low cost sharing and plans retain the majority of the benefit of lower POS prices. Some Medicaid MCOs and state Medicaid programs could see greater impact depending on their circumstances. There may also be some indirect impacts to commercial and Medicaid markets, including limiting incentives for prescription drug manufacturers to increase list prices in the future and the potential that manufacturers may choose to set lower list prices for new-to-market prescription drugs.

The Medicare bid process

To set premiums, all Part D plans first submit bids to CMS. These bids include cost estimates of:

The federal government provides subsidies to the program by way of a direct subsidy and a reinsurance subsidy. By law, the sum of these two subsidies is equal to 74.5% of the sum of the average standardized bid and average reinsurance estimate submitted by plans in their bids (in aggregate across the entire Part D program). Once all bids are submitted, CMS tabulates these averages and informs plans of their final premiums.

|

Standardized Bid =

Estimated Gross Drug Costs

- Beneficiary cost sharing - Net Federal Reinsurance - Rebates + Administrative Expense + Profit |

Beneficiary Premium =

Standardized bid

- Direct Subsidy + Supplemental premium |

The above equations illustrate how rebates directly reduce plan costs and therefore the bid amount, which in turn reduces premiums. This suggests the increase in rebates over time was likely a key contributor to slower growth in Part D plan premiums.

Implications for the Medicare program

This proposed rule released January 31, 2019, if finalized, would redirect the funds flowing through the Part D program. Several of the positive and negative transfers are imperfect offsets of one another. It is difficult to predict the full extent of the transfers created by this proposed rule in the absence of information about strategic behavior changes by prescription drug manufacturers and Part D plan sponsors in response to this rule. For example, behavior changes by plans could take the form of changes in benefit offerings and by manufacturers could involve changes to pricing processes. This information will only become available over time following implementation.

In the immediate term, the proposed rule states that it is possible that CMS may run a 2020 Part D bid cycle where bids could be submitted without knowledge of whether the proposal will be finalized with a January 1, 2020, effective date.28 Finalized safe harbor changes could affect the assumptions underlying plan sponsors’ bids, leading CMS to administer a one-time process to allow plans to update their bids for 2020.

Implications for beneficiaries

Patients will be impacted differently based on three factors: the plan in which they are enrolled, the prescription drugs they take, and whether or not they are eligible for an income-based subsidy to cover some or most of their cost sharing. The HHS OIG proposed rule notes “Under the CMS Actuary’s analysis, the majority of beneficiaries would see an increase in their total out-of-pocket payments and premium costs.”29 Milliman’s analysis suggests that a minority of beneficiaries will see cost-sharing reductions in excess of premium increases resulting from this rule, particularly non-low income beneficiaries using currently-rebated brand drugs, all else equal.30

Patients may also see impacts to formulary coverage and the types of plan designs offered by Part D plans. Some industry experts speculate that broader formulary coverage will exist absent a rebate incentive, while others speculate that high-cost prescription drugs that previously had a lower net cost to Part D plans due to high rebates may no longer be covered or could be more difficult to obtain because of implementation of other controls such as prior authorization. In addition, as soon as 2021, there will likely be a reduction in defined standard benefit parameters such as the deductible and initial coverage limit relative to what they would have been without this regulation, resulting in lower cost sharing for beneficiaries.

Implications for Part D plans

Part D plans will see varied impact which will depend on the characteristics of their enrolled populations and the contract terms with their PBMs specifying the level of control they have over formulary and contracting changes. Plans will need to consider whether they will experience utilization pattern changes that may result from any POS prescription drug price changes.

Plans will likely submit bids that include higher standardized bid amounts and lower reinsurance amounts than they would under current regulation, assuming current rebates are directly passed through as POS discounts. This will result in higher direct subsidy payments and slightly higher premiums for most plans, all else equal.31

Implications for prescription drug manufacturers

If the proposed rule is finalized, prescription drug manufacturers may need to adjust their contracting strategies as formulary decisions would likely shift toward prescription drugs with the lowest net costs to plans and patients.32 This shifting could include Part D plans preferring prescription drugs with low list prices that do not undergo frequent price increases.33 Still, the role of rebates in the commercial space could present challenges to lowering list prices because any reductions in price would impact all markets. Lowering list price would also limit a manufacturer’s ability to offer additional discounts to incentivize favorable formulary placement. Therefore, prescription drug manufacturers may choose to launch authorized generics to allow for differing list price and rebate strategies in different markets, or they may decide to delay action until they have more understanding of how Part D plans respond to the safe harbor changes included in the proposed rule.

However, even if list prices do not go down (or increase at a slower rate than in recent history), prescription drug manufacturers may see an increase in utilization of high-cost prescription drugs as the application of rebates at the POS will drive down cost sharing and may make these prescription drugs more affordable for patients. In addition, if fewer patients enter the coverage gap, prescription drug manufacturer costs may go down as a result of having to cover fewer patients in this coverage phase. Finally, beneficiaries will also remain in the gap longer, so that increased time in the gap may offset the reduction in costs due to fewer beneficiaries entering the gap.

Implications for PBMs

Currently, Part D plan and PBM arrangements are set up so that the majority (if not all) of the Current Manufacturer Rebates are passed through the PBM to the plan. Still, many large health plans own a PBM and some PBMs administer their own Part D plans.34 Therefore, the actions of PBMs will likely align with those of the Part D plans.

Significant uncertainty exists around how PBM operations could be affected by the proposed rule. The changes could complicate PBM claim operations and impact cash flows if PBMs were required to effectively pay out rebates by reducing POS prices prior to receiving rebate revenue from prescription drug manufacturers. While PBMs would not be able to retain rebates under the proposed rule, they would still be allowed to retain fixed fees for services provided to prescription drug manufacturers. However, they may try to generate more revenue to compensate for any lost rebates by shifting utilization to their mail order or specialty pharmacies.35

What comes next?

The proposed rule is open for comment through April 8, 2019. In addition to the three proposals discussed above, HHS OIG seeks comments on a number of other topics, including whether the removal of safe harbor protection of price reductions also should apply to prescription drugs payable under other HHS programs, such as Medicare Part B fee-for-service.

CMS will release its final 2020 Medicare Advantage and Part D Rate Announcement and final Call Letter by April 1, 2019, which would precede the close of the comment period on the HHS OIG proposed rule. Major rules, defined as those that are economically significant (including this proposed rule), typically must be made effective at least 60 days after the date of publication in the Federal Register. Therefore, HHS OIG would need to issue a final rule by the beginning of November 2019 for new policies to be effective January 1, 2020. Given this timing, there may be significant uncertainty around whether the proposals in this rule will be finalized and implemented for calendar year 2020 when Part D plans submit their bids.

Beyond Part D plan bids, the proposals, if finalized, are far-reaching and represent significant changes from the status quo. Health plans, PBMs, retail pharmacies, prescription drug wholesalers, and any number of entities that serve these organizations will, in some cases, need to re-orient entire business models and restructure back-end operations to manage the new paradigm. For them, implementation on January 1, 2020, may appear an impossible task; however, given this administration’s focus on lowering prescription drug costs, the impossible may indeed become reality.

1The full text of the proposed rule as published in the Federal Register is available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-02-06/pdf/2019-01026.pdf.

2Schondelmeyer, S.W. & Purvis, L. (September 2018). Trends in Retail Prices of Prescription Drugs Widely Used by Older Americans: 2017 Year-end Update. AARP Public Policy Institute. Retrieved February 6, 2019, from https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2018/09/trends-in-retail-prices-of-brand-name-prescription-drugs-year-end-update.pdf.

3HHS (March 8, 2016). Observations on Trends in Prescription Drug Spending. Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Retrieved February 5, 2019, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/observations-trends-prescription-drug-spending.

4The full text of the proposed rule is available at https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/safeharborregulations/012389.htm.

5The full text of the 1991 final rule is available at https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/safeharborregulations/072991.htm.

6The full text of the final rule as published in the Federal Register is available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/1999/11/19/99-29989/medicare-and-state-health-care-programs-fraud-and-abuse-clarification-of-the-initial-oig-safe-harbor.

7The full text of the final rule as expanded in 2002 and published in the Federal Register is available at https://oig.hhs.gov/authorities/docs/technical%20rule.pdf.

92018 Medicare Trustees Report, Table IV.B8, available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/Downloads/TR2018.pdf.

10Klaisner, J., Holcomb, K., & Filipek, T. (January 31, 2019). Impact of Potential Changes to the Treatment of Manufacturer Rebates, Appendix A1, Scenario 1. Milliman Client Report. Retrieved February 6, 2019, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/260591/MillimanReportImpactPartDRebateReform.pdf.

11CMS.gov. National Health Expenditure Data: 2017, Table 2. Retrieved February 7, 2019, from https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html.

122018 Medicare Trustees Report, Table IV.B8, available at https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/Downloads/TR2018.pdf.

13CMS.gov. Medicare Part D Spending Dashboard & Data. Retrieved February 7, 2019, from https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Information-on-Prescription-Drugs/MedicarePartD.html.

14See https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2019-02-06/pdf/2019-01026.pdf.

15HHS (November 28, 2017), Proposed Rule, op cit.

16Fiscal Year 2019 Budget of the U.S. Government. Retrieved February 6, 2019, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/budget-fy2019.pdf.

17Federal Register (April 16, 2018). Final Rule: Medicare Program; Contract Year 2019 Policy and Technical Changes to the Medicare Advantage, Medicare Cost Plan, Medicare Fee-for-Service, the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Programs, and the PACE Program. Retrieved February 6, 2019, from https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2018-04-16/pdf/2018-07179.pdf.

18HHS (May 2018). American Patients First. Retrieved February 6, 2019, from https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/AmericanPatientsFirst.pdf

19Federal Register (August 27, 2018). Medicare and State Health Care Programs: Fraud and Abuse; Request for Information Regarding the Anti-Kickback Statute and Beneficiary Inducements CMP. Retrieved February 6, 2019, from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2018-08-27/pdf/2018-18519.pdf.

20HHS (November 30, 2018). Proposed Rule: Modernizing Part D and Medicare Advantage to Lower Drug Prices and Reduce Out-of-Pocket Expenses. Retrieved February 6, 2019, from https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2018-25945.pdf.

21HHS (February 6, 2019), Proposed Rule, op cit.

22Rebates can also include payments from prescription drug manufacturers to wholesalers and pharmacies or payments from pharmacies to health plans. These rebates are not considered in this paper.

23HHS (November 30, 2018), Proposed Rule, op cit.

24Roehrig C. (April 2018). The Impact of Prescription Drug Rebates on Health Plans and Consumers. Altarum. Retrieved February 6, 2019, from https://altarum.org/sites/default/files/Altarum-Prescription-Drug-Rebate-Report_April-2018.pdf.

25CVS Health (October 1, 2018). SilverScript Insurance Company, a CVS health company, introduces three Medicare prescription drug plan options for 2019. News release. Retrieved February 6, 2019, from https://cvshealth.com/newsroom/press-releases/silverscript-insurance-company-cvs-health-company-introduces-three-medicare.

26Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (March 2018). Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy, Chapter 14: The Medicare Prescription Drug Program (Part D): Status Report. Retrieved February 6, 2019, from http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch14_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0.

28HHS (February 6, 2019), Proposed Rule, op cit.

29HHS (February 6, 2019), Proposed Rule, op cit.

30Klaisner, J. et al., op cit.

31For more information on potential financial impacts, see the Milliman report cited in the HHS OIG proposed rule as well as a forthcoming Milliman article which will describe plan considerations in greater detail.

32Klaisner, J. et al., op cit.

33Klaisner, J. et al., op cit.

34Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (March 2018), Chapter 14, op cit.