What is disruptive innovation?

The concept of disruptive innovation has attracted significant attention since it appeared in Clayton Christensen’s influential book “The Innovator’s Dilemma.” Yet its meaning is often misunderstood or misapplied. More than a decade after the book’s publication, Christensen revisited the theory in the pages of the Harvard Business Review. He and his co-authors emphasized that disruptive innovation begins with products creating low-end or new-market footholds that relentlessly move upmarket, eventually displacing established competitors.1 In other words, disruption starts when a company identifies and satisfies an unmet (and sometimes latent) need.

Take the automobile for example. In the late 19th century, cars were not a disruptive innovation. They were luxury items occupying the high-end of the transportation market. Most people continued using more affordable horse-drawn vehicles to travel. True industry disruption came in 1908 with the debut of the Ford Motor Company’s “Model T.” This lower-priced car changed the transportation industry by making automobiles an affordable replacement for horse-drawn transportation, creating a whole new tier of consumers.

More recently, Netflix is an example of disruptive innovation. Catering at first to a niche group of consumers with its web interface and mail-order delivery, Netflix didn’t appear to challenge Blockbuster, the industry leader in movie rentals. However, the advent of streaming technology enabled Netflix to completely re-think the business. Netflix’s ability to pivot quickly, along with the convenience, ease-of-use, and low price point of its offering, allowed it to quickly unseat Blockbuster.

Although disruption has been around for a long time, the pace has accelerated. We can look to the turnover of companies listed on the S&P 500 equity index as a measure of the change. On average, a listed company is replaced by a newcomer every two weeks. It has been estimated that over 40% of today’s Fortune 500 companies listed on the S&P 500 will no longer exist within 10 years.2

What leads to disruptive innovation?

Technology advancement and the digitization of information has played a large role in the disruption of industries and markets. However, it would be a mistake to attribute disruption solely to technology. There are several other factors underpinning disruptive innovation regardless of industry. An industry ripe for disruption typically exhibits one or more of the following dynamics.

Complex experiences

There are few industries as complex as healthcare. As noted by Jeffrey Braithwaite, professor of health systems research and president of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, “Healthcare is a complex adaptive system, meaning that the system’s performance and behaviour changes over time and cannot be completely understood by simply knowing about the individual components…No other industry or sector has the equivalent range and breadth—such intricate funding models, the multiple moving parts, the complicated clients with diverse needs, and so many options and interventions for any one person’s needs.”3

Many times, simple healthcare needs can lead consumers into a maze of appointments, practitioners, treatments, and locations. When that happens, it may lead consumers to decide it’s just not worth their time or money to deal with the healthcare system, potentially to the detriment of their health.

Against this backdrop, MinuteClinic was founded to provide convenient, high-quality access to routine healthcare needs. Located inside retail chains like CVS and Target, consumers can walk in without an appointment and receive care from a nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant. Services range from sports physicals to flu shots to the diagnosis and treatment of common illnesses such as bronchitis or strep throat. This model of care has proved to be popular. Since the inception of the first retail clinic more than 20 years ago, there are now nearly 3,000 such clinics in the United States.4

While MinuteClinics won’t put primary care providers out of business, the convenience of getting a flu shot while shopping may be the beginning of a disruptive innovation that leads to additional alternative care settings.

Consumer confusion

The insurance industry has a long history, dating back to ancient Babylon and enshrined in the Code of Hammurabi.5 Despite the social benefits of risk management, the industry’s participants and regulators have often called for increased transparency in product definition, pricing, and claims processing. With contracts full of legalese and jargon, insurance products are often viewed as complex and hard-to-understand. Sometimes it seems the insurance industry is more oriented toward the business side of things than appealing to customer needs.

Enter Lemonade, a company determined to make insurance loveable. Designed to be fast and simple–-90 seconds to get insured, three minutes to get paid–-it makes the entire customer lifecycle experience almost frictionless for consumers. Further, by donating the leftover premiums to a charity of the consumer’s choice, the company has repositioned insurance from being just a necessary risk management vehicle to one of societal good.

Redundant intermediaries

Once a staple of strip mall storefronts, most retail travel agencies have fallen victim to disruptive innovation. Traditionally, the travel agent acted as an intermediary, scouting prices and arranging itineraries for travelers. The advent of widespread internet access and sites like Expedia, Travelocity, and Orbitz made travel agents unnecessary middlemen. With just a few clicks, consumers compare their own flight prices and hotel accommodations, which often allows them to book with ease.

Travel agents are no longer the only source for learning about different destinations and experiences either. The proliferation of review sites and recommendations from other travelers on social media has diminished the expertise of agents. As “anywhere, anytime” technologies continue to develop, along with AI virtual assistants, the travel industry will continue to transform. This disruption will almost certainly continue to benefit the average consumer with increased convenience and lower cost travel experiences.

Limited access

There is no shortage of financial management firms in the world. Generally, many investment advisors may be most interested in working with high-net-worth clients who need a suite of services and are willing to pay the associated fees for high touch service. That strategy has left a large population of younger and/or less affluent potential investors looking for help to manage their finances easily, conveniently, and at a low cost. Robo-advisors are filling that gap.

Robo-advisors are algorithm-based automated platforms that provide financial management services. Although the use of technology to facilitate investing is not new, offering it directly to consumers is. Like other disruptive innovations, robo-advisor platforms like E Trade, TD Ameritrade, and Robinhood offer services at a fraction of the cost of traditional human advisors with increased convenience.6 As demographics shift in the market and younger, digitally savvy workers accumulate wealth, the disruption of wealth management may be here to stay.

Who benefits from disruptive models?

Consumers are an obvious beneficiary of disruptive innovation. The easy access, convenience, and lower costs of disruptive products meet their needs in a marketplace that may have previously had no way to service them.

Perhaps less intuitively, an argument can be made that all industry participants tend to benefit from disruption. While established entities may experience some upheaval, disruption forces them to revisit their business models and refocus on their core businesses. They have new opportunities to innovate existing products, invest in their workforce, and ensure they are serving consumers.

What is the business of healthcare?

Does history repeat itself? In business, it often appears to. Many victims of disruptive innovation made the mistake of defining their business by what they produced, rather than understanding what consumers wanted. This point was made powerfully by the scholar Theodore Levitt in his classic article “Marketing Myopia”, first published in the July/August 1960 issue of the Harvard Business Review.

“The railroads are in trouble today not because that need was filled by others (cars, trucks, airplanes, and even telephones) but because it was not filled by the railroads themselves. They let others take customers away from them because they assumed themselves to be in the railroad business rather than in the transportation business. The reason they defined their industry incorrectly was that they were railroad oriented instead of transportation oriented; they were product oriented instead of customer oriented...”7

The healthcare industry may find itself in a similar situation. While the human body may always need clinicians who can tend to ailments and cure disease, what people really want is health. Our current healthcare system is a means to an end, and an expensive one at that. National healthcare expenditures in the U.S. grew to $3.8 trillion in 2019, or $11,582 per person, and accounted for 17.7% of gross domestic product. It is projected to continue growing at an average annual rate of 5.4% and reach $6.2 trillion by 2028.8

The signals for disruption are present in the market, as noted in the MinuteClinic example at the beginning of this article. Our modern healthcare systems took shape in the early twentieth century, during a time when infectious diseases were the primary cause of mortality.9 Today, we understand that health is more than just biology. Environmental factors and social determinants play an important role in health outcomes. It has been reported that 90% of American healthcare expenditures10 and 70% of our mortality rate11 can be attributed to preventable chronic conditions. Yet the complexity of our healthcare system often lacks the incentives to create a consistent, consumer-focused model that meets modern needs.

Erosion of trust also appears to be an issue for the healthcare industry. In a review of historical polling data and surveys published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Robert Blendon and his co-authors wrote,

“We found that, as has been previously reported, public trust in the leaders of the U.S. medical profession has declined sharply over the past half century. In 1966, nearly three fourths (73%) of Americans said they had great confidence in the leaders of the medical profession. In 2012, only 34% expressed this view.”12

This general lack of trust may contribute to a reduction in healthy behaviors, ranging from medication adherence to following a care plan. Equally important, this lack of trust may be a barrier preventing consumer adoption of industry-led healthcare innovations.

As the healthcare industry works to improve the care delivery model while grappling with the perception of eroded trust, consumer expectations continue to evolve rapidly. Technological leaps in other industries have transformed aspects of everyday life. However, the healthcare industry lags conspicuously behind. A 2016 survey of US healthcare consumers found that over 50% of respondents would likely switch hospitals due to poor electronic communication.13 Interacting with the healthcare system continues to be far more complex and frustrating compared to consumer experiences from any other industry (e.g., retail, banking.) Consumers have come to expect frictionless interactions. For many, the healthcare system is not servicing their needs.

How will healthcare get disrupted?

In planning and policy, a “wicked problem” is a problem that is difficult or impossible to solve. Elements that factor into a wicked problem can include incomplete knowledge, the number of stakeholders and/or opinions involved, and how the problem intersects with other problems.

From an economic standpoint, a disruption of the healthcare industry is likely. Over the last decade, the cost of healthcare per person has been increasing approximately four percent, outpacing two to three percent GDP growth.14 This is a highly unsustainable environment. However, the strong financial performance of payers, providers, and pharma provides limited incentive for change.

Is this the wicked problem of healthcare? If the industry itself can’t be relied on to innovate, who will provide the necessary disruption to improve the system? Here are two likely candidates.

The healthcare consumer

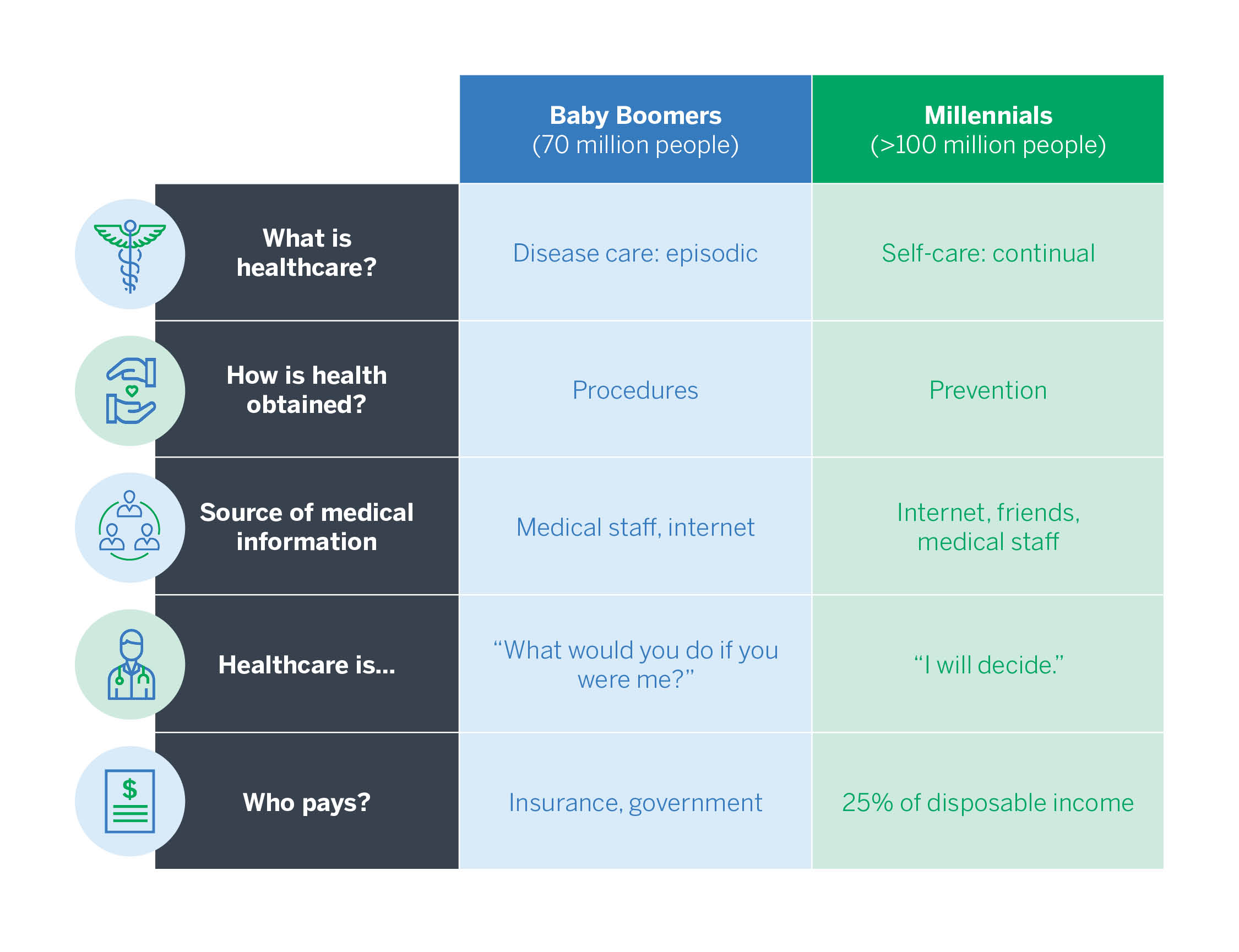

Changing demographics, consumer expectations, and technology are creating a new paradigm in which the current healthcare system cannot survive. The shift in thought and behavior is already evident in the difference between the Baby Boomer and Millennial generations, as shown below.

Attitudes toward healthcare: Baby Boomers versus Millennials15,16

The Millennial mindset has already led to an increased adoption of self-management health technologies ranging from activity trackers to devices for managing chronic conditions. Similarly, empathy networks (such as PatientsLikeMe17), telehealth technologies, and a heightened awareness of managing stress and lifestyle make these consumers likely agents for change in the healthcare industry.

Cohorts focused on health and wellness

Industry players don’t have adequate incentives for keeping individuals healthy. Over the past several years, regulatory efforts have been made to move the needle from “sick care” to true healthcare. A few examples:

- The HITECH Act and its Meaningful Use program incorporated financial incentives and financial penalties depending on the success care providers achieved in utilizing electronic health records. Among the program’s objectives? Improve coordination and quality of care while reducing costs and engaging patients in their own care.18

- The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act shifted the emphasis from payment for volume to payment for value.19 Traditionally, care providers are paid a fee for each service provided, regardless of outcome. New payment models reward providers who focus on the health outcomes of their patients and the quality of care and service their patients receive—not the number of times a service is rendered.

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have also introduced payment models designed to reward outcomes. Examples include, but are not limited to, bundled payments for an episode of care or the Medicare Shared Savings Program, which allows for the creation of Accountable Care Organizations that take on the financial risk, rewards, and sometimes penalties, of coordinating care for a population.20,21

There is still a long way to go in the shift from fee-for-service to value-based care. Other cohorts and communities who have a vested interest in an individual’s health may provide a faster path to disruption. Employers and large self-funded organizations can benefit significantly from the health of their individual employees. The increased interest in “whealth” (a portmanteau of wealth and health) management introduces life insurers and financial managers as other stakeholders who find value in the health and longevity of populations. Creative thinking from these outsiders may unleash the disruptive innovation that those within healthcare simply cannot provide.

The result of healthcare disruption

While past performance is not a guarantee of future results, it’s almost a sure bet that the process of disruptive innovation will improve healthcare as it has for so many other industries. As new products meet consumer-driven demand, health and economic gains will spread to stakeholders and beyond.

This does not negate the role of current industry participants. In the healthcare ecosystem, hospitals, insurers, providers, and more can build off of disruptive innovation, even if they haven’t created it themselves. Established players are beginning to take ownership of innovation, in some instances creating leadership roles to help improve their product offerings.22

Thankfully, in the midst of disruption existing digital health services are already finding ways to deliver simplified, cost-effective care on demand. However, they can’t transform the industry alone. Smart policy, private enterprise, and continued support of entrepreneurs will be necessary for society to reap the benefits of consumer-focused healthcare in the years to come.1Christensen, C.M., Raynor, M.E., & McDonald, R. (2015, December). What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://hbr.org/2015/12/what-is-disruptive-innovation

2Singularity University. (2020). The exponential leader’s guide to disruption. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://su.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Singularity-University-SU-EB-The-Exponential-Leaders-Guide-to-Disruption-EN.pdf

3Braithwaite, J. (2018). Changing how we think about healthcare improvement. BMJ. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2014

4County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. (2020, July 16). Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/take-action-to-improve-health/what-works-for-health/strategies/retail-clinics#footnote_31

5Investopedia. (n.d.). The history of insurance: From ancient Babylonia to the American colonies. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www.investopedia.com/articles/08/history-of-insurance.asp

6The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. (2018, June 14). The rise of the robo-advisor: How fintech is disrupting retirement. Knowledge@Wharton. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/rise-robo-advisor-fintech-disrupting-retirement/

7Levitt, T. (2004, July-August). Marketing myopia. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://hbr.org/2004/07/marketing-myopia

8Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020, March 24). National Health Expenditure Projections 2019-28. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www.cms.gov/files/document/national-health-expenditure-projections-2019-28.pdf

9At the start of the twentieth century, infectious diseases were the leading cause of mortality, accounting for nearly a third of all deaths. Mortality in the United States: Past, Present, and Future — Penn Wharton Budget Model (upenn.edu)

10 National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2021, January 12). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/costs/index.htm

11 Schmidt. H. (2016). Chapter 5: Chronic disease prevention and health promotion. In Barrett, D. H., Ortmann L.W., Dawson A, Saenz, C., Reis, A. Bolan, G, (Eds.), Public Health Ethics: Cases Spanning the Globe. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435779/

12 Robert J. Blendon, Sc.D., John M. Benson, M.A., and Joachim O. Hero, M.P.H. Public Trust in Physicians — U.S. Medicine in International Perspective | NEJM October 23, 2014 N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1570-1572 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1407373

13 Betts, D., Balan-Cohen, A., Shukla, M., Kumar, N. (2016). The value of patient experience: Hospitals with better patient reported experience perform better financially. Washington, D.C.: Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/life-sciences-health-care/us-dchs-the-value-of-patient-experience.pdf

14 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020, March). National Health Expenditure Projections 2019-28, Forecast Summary. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www.cms.gov/files/document/nhe-projections-2019-2028-forecast-summary.pdf

15Fronstin, P. Dretzka, E. (2018, March 5). Consumer engagement in health care among Millennials, Baby Boomers, and Generation X: Findings from the 2017 consumer engagement in health care survey. [Issue Brief, No. 444] Employee Benefit Research Institute. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from file:///Users/saraaldworth/Downloads/ebri_ib_444_millennialhealthcare-5mar18.pdf

16Sandle, T. (2017, July 6). Boomers, Gen Xers, Millennials, Gen Z: healthcare expectations. Digital Journal. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from http://www.digitaljournal.com/life/health/boomers-gen-xers-millennials-gen-z-healthcare-expectations/article/497028

17Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www.patientslikeme.com/

18What is the HITECH Act (hipaajournal.com)

19A Shift to Value-Based Healthcare | UIC Health Informatics

20Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative (BPCI) | CMS

22Humana Inc. (2018, August 27). Humana accelerates digital health and analytics capabilities [Press release]. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://press.humana.com/news/news-details/2018/accelerates-digital-health-analytics-capabilities/default.aspx#gsc.tab=0