Every year we see new images of devastation caused by hurricanes, floods, and other natural disasters. The frequency and severity of these tragedies have increased, and with climate change, we can expect this trend to continue. Developing nations, who have contributed little to the cause of climate change, are those most vulnerable to its impact—they experience more extreme events but lack the resources to combat their effects.

The disaster finance gap and the G7 commitment

At its recent meeting in Germany, the leaders of the Group of Seven (G7) countries recognized this inequity and committed to action. In addition to urgent progress in mitigating climate change itself, they noted the need for action to address the financial impact, stating, “We recognize the urgent need for scaling-up action and support to avert, minimize, and address loss and damage particularly in vulnerable developing countries.”1

The financial challenge is significant. In 2021, uninsured losses from natural catastrophe and weather risk totaled $213 billion.2 Analysis in 2018 noted that 59% of catastrophe losses in the developed world were uninsured, while in emerging economies this gap was 94%.3 Historically, the gap in the developing world has been addressed through international relief efforts. Unfortunately, these efforts often fall short, with funds arriving late and typically less than amounts pledged. The delay and uncertainty limit their impact, compounding the damage wrought by the initial catastrophe.

As the G7 leaders articulated, the world must do better. Fortunately, financial options are available to do so. Government-sponsored cat bonds are one option that has worked. We should expand their use and incorporate features to provide greater climate resilience over time.

The cat bond option

Insurance seems an obvious pathway for a financial approach to climate change remediation. However, the capital requirements necessary to cover the increased exposure limit the ability of traditional insurance to meet this need. A better solution would provide more options to attract capital. Ideally, the option would also provide financial investors with the advantages of risk diversification and risk tiering.

Catastrophe bonds, or cat bonds, meet many of these goals and should be a big part of the solution. Cat bonds function as fixed income instruments, where investors forfeit principal to the sponsor in the event of a disaster event and receive higher interest payments to compensate for this risk. Effectively, they operate like high-yield bonds where increased volatility and default risk result in increased interest (premium) rates to compensate the investor for this risk. Some cat bonds use an indemnity-based trigger like an excess of loss reinsurance contract, reimbursing losses suffered by the underlying sponsor caused by a covered natural catastrophe. Others use a parametric structure, where the payout is based on an objective trigger related to the catastrophic risk borne by the sponsor, such as wind speed, industry losses, or rainfall.4

The sponsor, which could be a primary insurer, reinsurer, captive, international financial institution, corporate entity, or sovereign entity, typically creates a special purpose vehicle to issue the bond. Once the bond is issued, the investment capital is collateralized in highly rated securities such as U.S. Treasuries. If a triggering event occurs, the collateral is released to the sponsor. If it does not occur over the bond term, investors receive their money back along with the premium payments plus interest over the term of the bond. In this case, the premium payments received reflect both a market interest rate as well as an amount that represents the underlying risk margin.

Cat bonds incorporate several of the ideal characteristics of an insurance-based mechanism to mitigate economic consequences of natural catastrophes. They greatly expand potential risk-taking capacity by opening investment to the financial markets; they draw on insurance, investment, and governmental funds. When structured with parametric triggers, they offer prompt and certain funding through collateralized holding and contractually defined payout criteria, and they are malleable instruments that are potentially applicable to a variety of climate-related risks.

Successful cat bonds through World Bank

Government-sponsored cat bonds, a subset of the cat bond market, are particularly relevant to address the growing risks in the developing world. This is not a new concept. In fact, government-sponsored cat bonds have been in place for several years and where used have worked as intended. These bonds have provided timely payouts to governments to address critical needs following disasters. At the same time, investors have enjoyed positive returns and have shown the capacity to do more. Moreover, because the underlying risks are in the developing world, these bonds provide a risk diversification benefit for cat bond investors since most cat bonds cover U.S.-based risks.

To date, the World Bank has facilitated most of these bonds. The World Bank is the largest world financial institution devoted to providing financial assistance to developing countries, and the organization has been at the forefront of deploying financial instruments to assist the disparate needs of developing nations. Along with their institutional mandate, the World Bank has unique characteristics that allow them to design and issue cat bonds for its clients. They are a highly respected organization with extensive experience, thus providing their cat bonds’ issuances greater investor credibility. Also, since the World Bank is AAA rated and can issue cat bonds under their “capital-at-risk” notes program, they can implement the structure without a special purpose vehicle, and they have more flexibility with the use of the funds. The World Bank sits between government sponsors and institutional investors, acting in concert with structuring agents to design and issue bond structures that then sit on the World Bank’s balance sheet and serve as a hedge against their underlying coverage for the government sponsor.

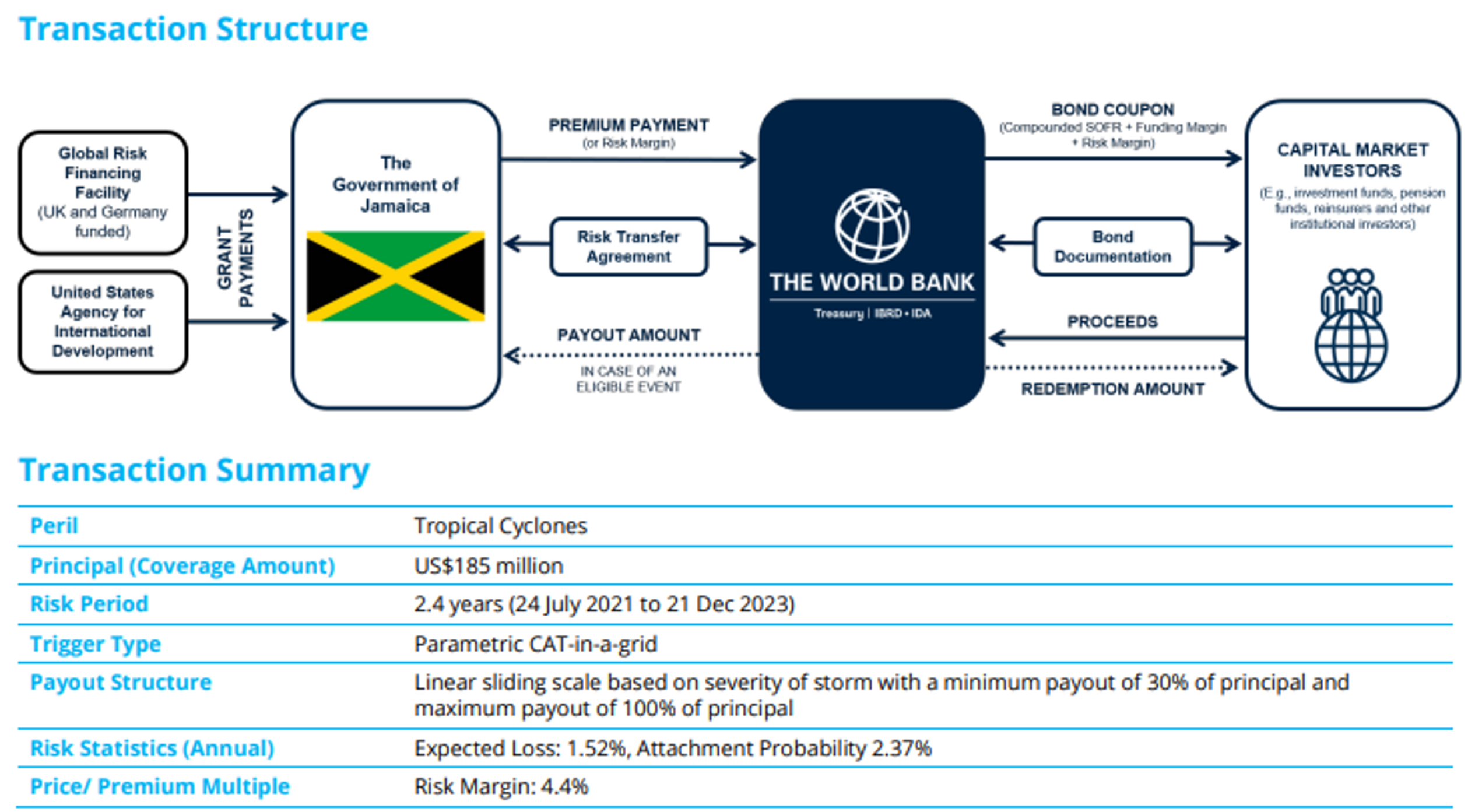

The following illustrates the structure of Jamaica’s cat bond covering tropical cyclones with the World Bank:

Figure 1: Structure for the World Bank’s Jamaican cat bond5

The World Bank’s cat bonds have tended to fit into two categories: cat bonds sponsored by individual countries, such as Mexico, the Philippines, and Jamaica; and bonds for risk pools for groups of countries such as the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF).6 Whether individual or pooled, bonds cover natural disasters such as cyclones, earthquakes, and floods, and they are parametric instruments that pay out specified amounts based on externally measured aspects of the natural disaster. The exact payout terms of cat bonds are private, but the World Bank publicized general details on the payout structure of the Jamaican cat bond which exemplify the methods of parametric payouts witnessed in government-sponsored cat bonds. The bond’s structure divides Jamaica and its immediate surroundings into a grid with nineteen distinct sections. Each section then has a distinct payout trigger if a storm passes through it based on the central barometric pressure of the storm.7 Sectioning off the country into distinct areas can allow the bond’s risk target to be tailored to Jamaica’s different geographical features, population densities, and local infrastructures. The bond also uses an objective and easily measurable meteorological parameter (barometric pressure) rather than actual economic or insured losses because the former is much simpler to calculate and a correlated proxy for the latter, enabling significantly faster and more efficient payout.

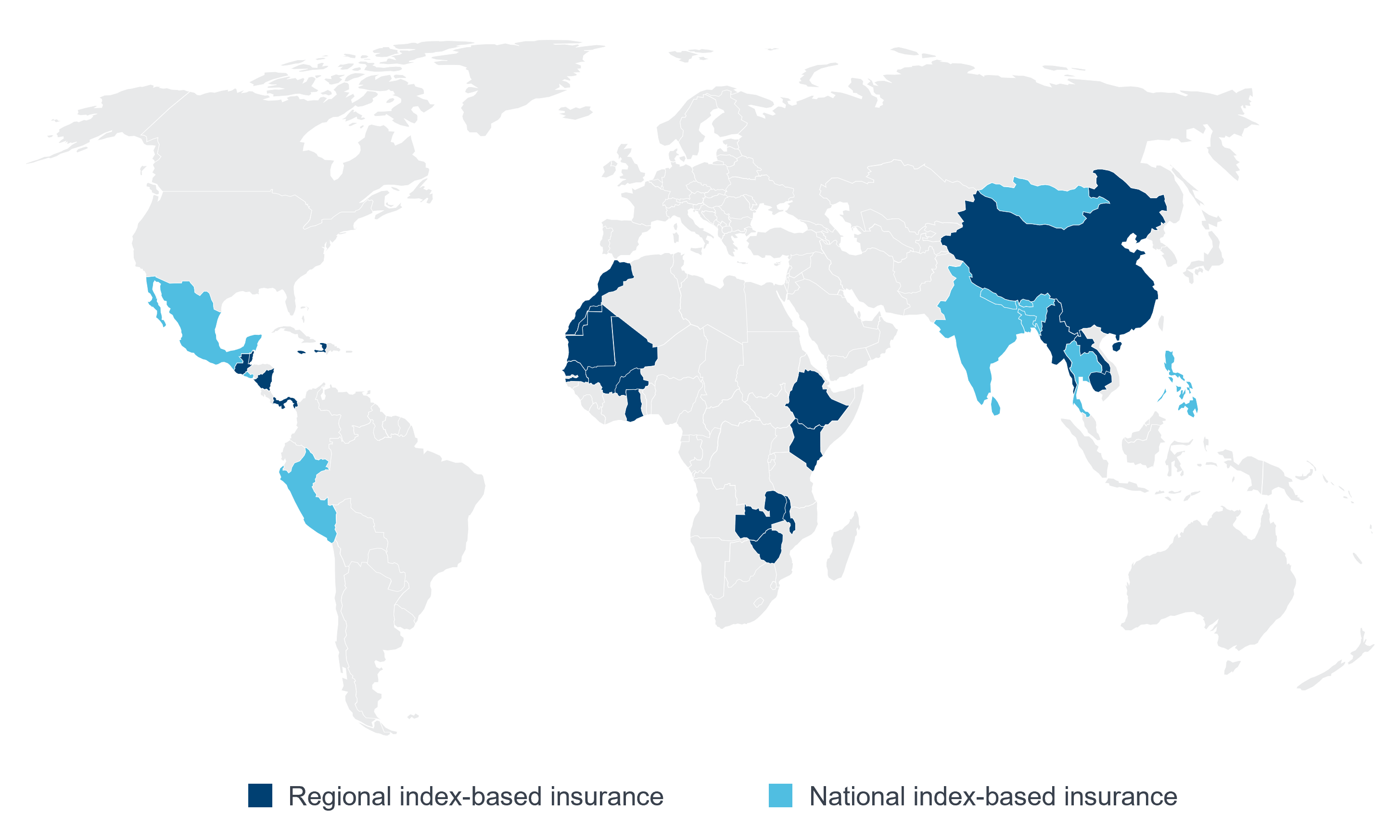

Examples of climate risk insurance

The highlighted countries have implemented at least one type of climate risk insurance. Many of these have been facilitated with the support of the World Bank or with a nonprofit organization.8

Progress, but more is required to meet the global need

Though government-sponsored cat bonds have the potential to mitigate the catastrophic effects of climate change in developing nations, as a global solution they have proven more attractive in theory than in practice. While growing, the broader cat bond market itself remains relatively small with typically fewer than 100 offerings per year.9 The vast majority of these are issued by private companies to cover tail risks in mature economies for insured catastrophes like Atlantic hurricanes, Pacific cyclones, or California earthquakes. The World Bank, which is the most active facilitator of risk management programs in the developing world, has facilitated one or two transactions per year. These transactions have been significant in their size, as the World Bank estimates that it has transferred roughly $3.6 billion worth of risk to date—but they are not yet prevalent in number. This small number of transactions is a barrier to the potential expansion of these offering to a wider pool of investors.10

There are a few intertwined reasons why government-sponsored cat bonds have been so limited.

- Cat bonds are highly complex investment vehicles and still relatively new to most of the world. Organizations like the World Bank can only create funds through forging relationships with governments, which takes time and, especially in developing nations, can break quickly when new leaders emerge with new sets of priorities.

- Cat bonds are also costly instruments with a long-term focus—they require significant setup costs and large premiums. Developing countries have many economic challenges, and cat bond premiums and set-up costs compete with other short-term priorities.

- There is insufficient catastrophe modeling available to price certain developing market risks. Climate-related catastrophes that are commonly covered by the insurance market, such as Atlantic hurricanes, U.S. and Japanese earthquakes, and Australian typhoons have a robust industry of modeling companies that inform insurers/investors of potential risks. The climate-related catastrophes faced by developing countries—new geographies of tropical cyclones and earthquakes, famine, drought, flooding, crop loss, wildlife extinction, deforestation, heat waves, and more—have considerably less modeling infrastructure due to a comparative lack of industry demand.

Finally, the cat bond as an investment option is currently focused on a subset of investors with specific expertise and sufficient capital. Expanding access to more capital sources would allow for greater risk transfer. Such expansion would likely first require more growth under the current structure, followed by structural changes to provide more options. More growth would result in a larger number of risks covered, as well as an increasing diversity in those risks. This would provide the potential to structure investment options covering a diversified set of risks. While recognizing the complexity that underlies cat bonds, this could open this asset class to a much broader array of investors and investment types.

Action to do more

G7 commitments should include action to expand government sponsored cat bonds. The structure provided through the World Bank has shown success—investors have attained reasonable returns and countries have received needed funds when catastrophe thresholds were triggered. However, few individual countries or groups of countries have embraced the cat bond structure. The global need is much greater and will continue to grow with the increasing impacts of climate change.

A future with more transfers of these catastrophic risks will benefit economies and populations across the globe, lessening both the economic impact of catastrophic events for developing countries, as well as the need for reactive and less effective emergency relief from the rest of the world. Getting to this better future requires change to drive greater demand for coverage from the developing world, and a corresponding increase in the supply of capital to take on the risk.

Visibility and efficiency are fundamental needs for the cat bond structure to grow. For both developing countries and mature economies, action here includes the following:

Visibility: Government leaders across the globe must be aware of the cat bond structure and its ability to help manage catastrophe risks. The benefit of quick access to defined amounts can help countries navigate risks, including those risks that are increasing with climate change. The funds can mean the difference between a quick recovery and a prolonged downward spiral.

Expertise: The cat bond structure is complex. However, this should not be a barrier for countries to take advantage of this tool. Expertise should be as transparent as possible, and accessible across geographies. Experts should be incented to share their knowledge with leaders across national boundaries. Loss of a key individual in one geography should not derail progress.

Modeling: The cat bond structure is amenable to a wide variety of potential perils in different geographies but requires reliable models for adequate pricing. Though catastrophe modeling is available for many risks in different parts of the world, this work must continue to include more perils and be more regionally specific. Quality models will be important to provide confidence to both the country sponsors and the investors that the bonds are priced fairly. In addition, models that incorporate longer time periods and account for climate change trends will become increasingly important. Modeling experts can leverage their varied expertise in modeling, simulation, pricing, and risk analysis to develop new models for risks so that they may be covered by prospective cat bonds.

Cost: While the benefits are significant, cat bonds come with a cost. For developing countries, this cost is weighed against competing priorities, many of which are connected to political agendas. Costs for cat bonds cannot be completely eliminated but keeping costs as low as possible is essential. Costs include both the overhead costs to initiate and operate the bonds and the premium cost incorporated in the bonds to pay investors. The World Bank structure is well suited to minimize the operational costs. Expanding the expertise of the bond structures will also help. Premium costs cannot be eliminated, but effective modeling will help ensure these are fair costs for the transfer of risk.

G7 leaders can prioritize these actions to increase visibility and efficiency. However, even more is needed. Ultimately, subsidies should be incorporated to reduce costs to affordable levels and stimulate growth of government cat bonds in the developing world. G7 commitments can play a central role here. As outlined below, subsidies can come in different forms from different entities, and can incorporate incentives.

Subsidies and targeted incentives

Should the developed world do more to subsidize the premium costs for developing countries? A strong case can be made that they should. First, the benefits of relief provided through a cat bond trigger accrue beyond the affected country. The proceeds lower the need for reactive relief funding, and the greater economic stability in the affected region benefits the global economy. Second, a subsidy provides a response to the global inequity of the climate change challenge, where countries who contributed little to the cause are greatly impacted by the result. Finally, creative structuring of subsidies can incentivize climate resilience or carbon reduction investments that provide benefits beyond the affected region.

These arguments align with the themes from the G7 leaders, who noted their meeting came at a time when we are at a “critical juncture for the global community, to make progress towards an equitable world.”

Effectively, support would translate to subsidies for developing nations, reducing the premium cost of catastrophic coverage for the developing countries least able to afford it. Creative subsidy options should be considered. Direct support of premium payments is one option, which has been employed in the World Bank’s cat bond for Jamaica. Tax-favored status of cat bond investments is another approach that would increase investor demand, lowering the necessary return from the bond and thus reducing the premium payments or cost to the sponsoring country.

The source of potential subsidies is not limited to G7 countries or other governments in the developed world. Nonprofit organizations could play a major role and facilitate support from individual charitable donations. With expansion and set-up work, cat bonds could also be combined into pooled investment structures to take advantage of the diversification across perils and geographies, opening this investment option to a wider pool.

Creative options can also expand the benefits of the cat bond structure to all parties. One option is to link the cat bond, and its associated premium, to climate resiliency investments by the sponsoring country. In this case the underlying subsidy reflected in the premium would be available only if the sponsoring country committed to resiliency action. For example, a country receiving premium support would commit to action to be better positioned to withstand a flood or hurricane in the future. This action benefits everyone, as the investments would reduce the risk of perils over time and the associated human suffering and economic impact.

Another option is linking the cat bond structure to investments in green energy and other initiatives to reduce the carbon footprint of the sponsoring country. In this case, the underlying subsidy would be available only if the sponsoring country committed to address carbon emissions through objectively measurable means. Climate change is a global challenge, and any single country is less motivated to act if other countries do not follow. More broadly, the challenge to address climate change may pit regions of the world against each other. For example, some countries in the developed world may be less incented to act if they believe developing nations will advance without limiting carbon output. Cat bond structures can be a tool to bridge this gap. Structures that incent carbon reduction investments can result in a win-win, incenting the developing world to act, and providing them an economic incentive to do so. In a future with an increasing role for carbon credits and carbon offsets, these could be connected to cat bond investments and subsidies.

Conclusion

An ideal solution for closing the catastrophe financing gap would be pooling risks across countries and perils through investment structures that would tap into the broader capital markets.

While the ideal solution may be a longer-term goal, cat bonds are a structure available to transition disaster costs in the developing world from reactive and insufficient relief efforts to proactive and efficient risk transfer solutions. Governments in developing countries have successfully used these structures with the help of the World Bank. However, much more is needed. This represents a prime use case for the G7 potential commitment of $100 billion toward climate finance.11

Expanding this market will trigger progress toward the ideal solution. Growth will bring interest from additional investors, with the potential for more financing options, including options for individual investors, ESG investment funds, and options with varying layers of risk tiering based on the covered catastrophe. Finally, financing options could be structured to incentivize climate resilience and carbon reduction initiatives in developing nations—a true win-win outcome with global long-term benefits.

This white paper was written as part of GUTSI—the Ground-Up Think Tank for Social Impact—an employee-led initiative that draws on Milliman’s entrepreneurial culture to find innovative solutions to global challenges.

1 Steve Evans, “G7 commits to scale up climate and disaster risk finance and insurance,” Artemis.bm June 29, 2022, https://www.artemis.bm/news/g7-commits-to-scale-up-climate-and-disaster-risk-finance-and-insurance/.

2 Aon: $343 Billion in Global Weather-, Catastrophe-Related Economic Losses Reported in 2021, Up From $297 Billion in 2020, Aon plc - Aon: $343 Billion in Global Weather-, Catastrophe-Related Economic Losses Reported in 2021, Up From $297 Billion in 2020.

3 “Closing the Natural Catastrophe Protection Gap,” Swiss Re Institute, March 17, 2018, https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/topics-and-risk-dialogues/climate-and-natural-catastrophe-risk/Closing-the-natural-catastrophe-protection-gap.html. For other statistics and discussion over the global insurance gap, see L.S. Howard, “Insurance Protection Gap is Growing Global Problem; Swiss Re, RenRe & WTW Comment,” Insurance Journal January 17, 2018, https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/international/2018/01/17/477266.htm; “Extreme Weather Risks: Restore People’s Lives,” Munich Re, retrieved July 7, 2022, https://www.munichre.com/en/risks/extreme-weather.html; “Risks Posed by Natural Disasters,” Munich Re, retrieved July 7, 2022, https://www.munichre.com/en/risks/natural-disasters-losses-are-trending-upwards.html.

4 Cat bonds usually have what is called a parametric trigger. With a parametric insurance contract, a party is buying a predefined amount of protection which will pay out based on predefined terms. Since predictability of payout and speed of payout are vital for cat bonds, a parametric approach provides certainty that a financial payment will be made when certain conditions are met. For further information, see “What is Parametric Insurance?,” Artemis.bm, retrieved July 7, 2022, https://www.artemis.bm/library/what-is-parametric-insurance/.

5 “World Bank Catastrophe Bond provides Jamaica with Financial Protection against Tropical Cyclones,” World Bank, retrieved July 7, 2022, https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/43a111757d3b1ff1cabde80ee7eb0535-0340012021/original/Case-Study-Jamaica-Cat-Bond.pdf.

6 Other risk pools funded by the World Bank, such as the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Insurance Company (PCRIC) and the Southeast Asia Disaster Risk Insurance Facility (SEADRIF), have not yet developed these instruments, but may do so as the programs mature and gain capitalization. .

7 Carlos Felipe Jaramillo and Jingdong Hua, “How the Catastrophe Bond Market Is Supporting Financial Resilience in Jamaica,” Financial Protection Forum December 22, 2021, https://www.financialprotectionforum.org/blog/how-the-catastrophe-bond-market-is-supporting-financial-resilience-in-jamaica.

8 A useful summary of these offerings is found in Thomas Hirsch and Vera Hampel, “Climate Risk Insurance and Risk Financing in the Context of Climate Justice: A Manual for Development and Humanitarian Aid Practitioners,” ActAlliance, 2020, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Climate-Risk-Insurance-Manual_English-1.pdf.

9 For example, 2021 had witnessed a record of 84 bonds. See “Catastrophe bond market achieves new annual record,” PR Newswire, January 4, 2022, https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/catastrophe-bond-market-achieves-new-annual-record-301453183.html.

10

Cat bonds for developing nations could be readily marketable to a wide pool of investors. For example, The World Bank’s bond offerings tend to get good subscription from investors and feature relatively cheap coupons, for example. Individual investors would also be drawn to these investments due to interests in ESG and charitable investing, and developing countries would certainly welcome outside capital to assist with climate remediation. With growth of the structure, it seems logical that investment structures like bond mutual funds or collateralized debt obligations could be leveraged to make these investments available for individual investors. For a discussion of the potential for CDOs to facilitate catastrophe reinsurance, see Aaron Koch, “A New Model for Weathering Risk: CDOs For Natural Catastrophes,” Casualty Actuarial Society E-Forum, Spring 2015, https://www.casact.org/sites/default/files/database/forum_15spforum_koch.pdf.

Yet bond mutual funds require the selection of a representative group of bonds intended to mirror the return of a larger sector, and ETFs would require the further step of market-tradable bonds. Collateralized debt obligations have a negative reputation from the subprime mortgage crisis of the mid-2000s. But even if regulated and/or rebranded, there needs to be sufficient diversity in the underlying investment pool to allow for tranches of different risk levels. Neither is remotely possible in a market sector where the number of instruments can be counted on one’s fingers.

11 Evans, “G7 commits to scale up climate and disaster risk finance and insurance.”