A more flexible interpretation for states, but new compliance requirements will apply

Executive Summary

Previous guidance issued through Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)1,2,3 issued by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS), outlining how state Medicaid programs can qualify for the 6.2% increase in the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP), put significant restrictions on a state’s ability to make beneficiary eligibility decisions and limited a state’s ability to make programmatic changes in response to the recent budgetary challenges. CMS has now published a rule updating this interpretation, creating new obligations for states in order to continue receiving the enhanced FMAP.

In an Interim Final Rule with Request for Comments (IFC), published on October 28, 2020,4 CMS announced an updated interpretation of the Maintenance of Effort (MOE) provision related to the temporary 6.2% increase in Medicaid FMAP for states.5 This Milliman white paper provides an overview of the new MOE requirements and programmatic changes allowed by the statute. CMS explains in the IFC6 that it has considered several possible reasonable interpretations of the MOE provision. Based upon comments from states and its review of possible alternative interpretations, CMS is now adopting a “blended approach” that is somewhat different from its original interpretation.

Unlike the previous regulation, which severely restricted a state's ability to move beneficiaries into new eligibility categories, the new interpretation enables states to make changes in their programs, not only in moving beneficiaries into their correct eligibility category (with caveats discussed below and while maintaining eligibility), but also allowing programmatic changes that may be needed in these challenging budgetary times. CMS states that this interpretation is intended to ease the administrative burden anticipated by the previous interpretation of the MOE both during and after the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (PHE).7

New “Blended Approach” for CMS Interpretation of Maintenance of Effort

Generally, under the IFC, states are now required to move beneficiaries to another, more appropriate category so long as benefits are not reduced to a lower tier.

- Movement within a tier or to a higher tier is required if the new group is more appropriate given a beneficiary’s new circumstances.

- If a beneficiary reports a resource change that would result in loss of eligibility under a coverage group and the beneficiary is not eligible for any other same or higher tier group, then the state must continue to provide that individual with the coverage available to beneficiaries in the original group.

- Despite these requirements, certain changes are permitted if voluntarily requested by the beneficiary.

The IFC establishes three tiers of benefits for assessing a change to a beneficiary’s eligibility status:

- Tier 1: Groups with minimum essential coverage.

- Tier 2: Groups without minimum essential coverage but with COVID-19 testing and treatment.

- Tier 3: Limited-benefit coverage groups.

The IFC also discusses requirements for coverage of COVID-19 testing and treatment for certain eligibility groups (including exceptions) during the PHE, as well as the availability of additional FMAP for covering these services for certain groups following the end of the PHE.

The previous interpretation of the MOE applied until the regulation was published by the Federal Register (November 6, 2020). The new interpretation applies from that publication day until the end of the month when the PHE ends. CMS is accepting comments on this IFC until January 4, 2021. Items not specifically addressed in this IFC may be addressed in statute or in previous FAQs released by CMS.

Background

Section 6008 of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA)8 provides a temporary 6.2% increase in FMAP for states and territories during the COVID-19 PHE. The MOE language in the statute says that a state could not make any changes in its “eligibility standards, methodologies, or procedures under the State plan of such State…” that “…are more restrictive …than the eligibility standards, methodologies, or procedures, respectively, under such plan (or waiver) as in effect on January 1, 2020.”9 CMS issued several FAQs outlining its interpretation of the MOE provision of the FFCRA. CMS’s original interpretation of this statue was that states could not terminate any individual from Medicaid, reduce benefits, or increase cost-sharing amounts during the COVID-19 PHE.10

Based on state concerns regarding the inability to make changes in their Medicaid programs during the PHE, especially as they face difficult budget constraints, CMS revised its original interpretation of the requirements under Section 6008 of the FFCRA. CMS has determined the language in Section 6008(b)(3) of the FFCRA to be “somewhat ambiguous,”11 recognizing that the original interpretation could “impede the routine, orderly transition of beneficiaries between eligibility groups, and could lead to significant backlogs in redeterminations and appeals after the PHE for COVID-19 ends.”12 In addition, comments from states indicated that the “existing interpretation severely limits state flexibility to control program costs in the face of growing budgetary constraints.”13

Prior to releasing the most recent IFC, CMS discussed another potential option referred to as “enrollment interpretation.” Under this option a state would be able to make programmatic changes, eliminate optional benefit coverage, and/or increase cost sharing (except COVID-19 claims).14 This interpretation would allow states to make individual beneficiary changes short of disenrollment. Because this interpretation may result in a negative impact on certain beneficiaries, CMS has declined it.15

As an alternative to the enrollment interpretation scenario described above, CMS announced in this IFC its adoption of a “blended approach” as discussed in detail below. The stated goal of this blended approach is to grant flexibility to states in making decisions for the “proper and efficient operation” of their Medicaid state plans, while at the same time balancing and protecting the needs of beneficiaries and providers.16

To support the blended approach, the IFC also adds a new subpart that includes a new definition of “enrolled for benefits” and utilizes the Minimum Essential Coverage (MEC) determinations:

- Validly enrolled (enrolled for benefits): The beneficiary was enrolled in Medicaid based on a determination of eligibility, including during the retroactive eligibility period, and the beneficiary was not erroneously granted eligibility at the point of application or last redetermination because of agency error or fraud.17

- Minimum Essential Coverage (MEC):18 Coverage that is provided under Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are considered MEC under Section 5000A(f) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 (Code), with the exception of the following eligibility categories providing less than comprehensive coverage:19

- Family planning services

- Tuberculosis-related services

- Pregnancy-related services (if covered benefits are determined to be not equivalent to full Medicaid coverage)

State actions required under the new “blended approach”

Under the “blended approach,” states must take several actions to maintain the enhanced FMAP:

- States must maintain beneficiary enrollment in an eligibility group that provides one of three tiers of coverage (see below) through the end of the month in which the PHE ends.

- States are not required to provide the exact same (or greater) amount, duration, and scope of benefits nor to maintain the cost-sharing levels. However, the following protections must be in place:

- Beneficiaries who had access to MEC must retain access to MEC but the benefits do not have to be identical.

- Beneficiaries who had access to testing and treatment services for COVID-19 must maintain their access to those services.

- The definition of “enrolled for benefits” is now interpreted as “validly enrolled.” This distinction enables Medicaid agencies to terminate eligibility for individuals who were not “validly enrolled” due to agency error, fraud, or abuse. All notification and hearing rights related to eligibility termination must remain in effect.

- Rules for maintenance of coverage will be based on whether a Medicaid beneficiary is covered in one of three tiers of benefits:

- Tier 1: Medicaid coverage that meets the definition of MEC.20

- Tier 2: Coverage not defined as MEC but robust enough to provide access to coverage of both testing services and treatment for COVID-19.21

- Tier 3: Coverage that is not MEC and that does not cover testing services and treatment for COVID-19, such as limited benefits like family planning.22 Note:

- States may not move a beneficiary from one Tier 3 eligibility group to another Tier 3 eligibility group.23

- Certain individuals who are eligible for optional eligibility groups, such as family planning, might be eligible for the “uninsured” group in order to receive COVID-19 coverage.24

- Beneficiaries in each benefit tier can request a voluntary transition to a different eligibility group for which they qualify even if the move would not meet the above requirements.25

- If a beneficiary who was validly enrolled is later determined ineligible for Medicaid prior to the end of the PHE, the state must continue to provide the same coverage that the individual would have received absent the determination of ineligibility.26

- If a beneficiary would have been determined ineligible because of a policy or procedure (failure to respond to a request for information) then the beneficiary must be maintained in that person's original eligibility group.27

- The previous interpretation of the MOE applies until November 6, 2020, the date the regulation was published in the Federal Register. The new interpretation, §433.400(c)(2) and (3), will apply from that day until the end of the month when the PHE ends. All other provisions become effective on November 2, 2020.

Risk of Negative Findings in a PERM Audit

Following a temporary suspension due to the PHE, CMS has resumed its program integrity efforts under the Payment Error Rate Measurement (PERM) program. States that do not carefully assure compliance with the new interpretation of the MOE requirements may be at risk under a PERM audit for incorrect eligibility determinations and could be liable for the payments made for services to which a beneficiary was not entitled.28

Coverage examples

The IFC provides several examples of the impact of the blended approach and new proposed regulations.

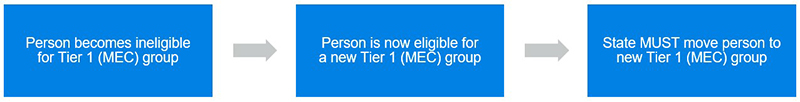

Figure 1: Tier 1 Example29

Tier 1 example: A person who ages out of the original eligibility group for children under age 19 must be moved to the adult group (if there is an adult group that person is eligible for), even if the adult group coverage has different benefits and cost sharing, because both meet the definition of MEC as long as the state has expanded eligibility for the adult population.

If a person becomes ineligible for a group that provides MEC and the state finds him or her eligible for coverage that does not meet the definition of MEC then the state may not move the beneficiary to the new group and must maintain the beneficiary’s access to coverage meeting the definition of MEC.

Other examples of this rule:

- A beneficiary enrolled in the adult group on or after March 18, 2020, who becomes eligible for a Medicare Savings Program (MSP) eligibility group, may be moved to the MSP because the MSP qualifies as a MEC.30

- A person who is originally eligible under the eligibility group for children under age 19 or the adult group cannot be moved to a limited benefit group such as family planning and family planning-related services because these groups would not qualify as MEC.

Figure 2: Tier 2 Example31

- Tier 2 example: A woman receiving postpartum coverage (42 CFR 435.116) in a state where this coverage is not considered to be a MEC must be moved to the adult group to the extent the state has elected that group (42 CFR 435.119) at the end of the postpartum period.32,33 If the state has not expanded coverage for the adult group, and the postpartum woman would be eligible through a limited benefit Section 1115 demonstration that provides access to COVID-19 testing and treatment, then the beneficiary must be moved to that category.

- However, if a postpartum woman is not eligible for any other Tier 1 or Tier 2 categories, the state must not move the woman and the state will be required to continue her coverage until the end of the PHE.

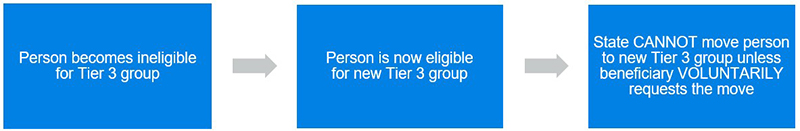

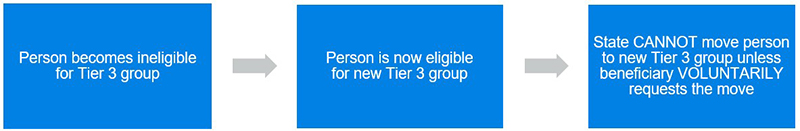

Figure 3: Tier 3 Example34

If a person loses eligibility for a Tier 3 coverage group, but is now eligible for a higher tier group, the state must move the beneficiary to a higher tier. However, a state must not move an individual among various Tier 3 groups, because Tier 3 groups have more limited yet widely varying benefits and are not interchangeable like Tier 1 groups (which are always MEC) and Tier 2 groups (which always include COVID-19 testing and treatment).

Tier 3 example: An individual loses eligibility for family planning benefits only but is now eligible for a group that focuses on preventing the progression of a specific disease. The state must not move the individual to the disease-specific group. The individual stays in the family planning benefits group, unless the individual voluntarily requests a move to the disease-specific group.

Note that an individual may be eligible for coverage in the optional COVID-19 testing group, in addition to another Tier 3 group, and can be enrolled in both of these limited-benefit groups if eligible.

Other enrollment-related changes under the IFC

Changes to benefits, cost sharing, and Post Eligibility Treatment of Income (PETI)35

States may make changes in their coverage, cost-sharing, and beneficiary liability terms provided the changes do not violate the individual beneficiary protections or the requirements to cover COVID-19 testing and treatment.

States are still required to follow all advance notice requirements. States may:

- Eliminate an optional benefit from its state plan such as adult dental

- Change the scope of benefits provided, including prior authorization criteria

- Establish or increase cost sharing and increase beneficiary obligations under the PETI rules, thus making the beneficiary responsible for more of the costs of institutional or home and community-based services (HCBS) care. For example, the minimum needs allowance for an institutionalized individual is $30/month; however, some states allow the beneficiary to retain more than the $30/month. The state can change the PETI rules to reduce the current amount to $30/month. 36

Exceptions to maintaining enrollment37

Despite the strict requirements to maintain eligibility as a condition of receiving the enhanced FMAP, several situations remain where a beneficiary may be terminated even during the COVID-19 PHE, including:

- If the beneficiary was not “validly enrolled”

- If the beneficiary requests voluntary termination

- If the beneficiary dies

- If the beneficiary no longer lives in the state

Conclusion

While this regulation provides significant flexibility to states under the MOE requirements, it still requires a careful review of eligibility determination processes, especially where a change of status occurs during the PHE. It may also require submitting clarifying questions to CMS particularly around the intersection of CHIP and Medicaid. Given the different categories and administration of CHIP across the country, and the fact that the IFC does not appear to address a beneficiary moving from Medicaid to CHIP, it would be important to clarify that issue.

The new blended approach to MOE will enable states to more accurately implement changed eligibility determinations during the PHE. This should result in the need for fewer eligibility changes after the PHE ends (to correct the temporary eligibility determinations mandated during the PHE), thus requiring less resources and a shorter period of time for the transition back to normal program operations.

1Medicaid (June 30, 2020). COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for State Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Agencies. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/downloads/covid-19-faqs.pdf.

2Medicaid (April 13, 2020). Families First Coronavirus Response Act – Increased FMAP FAQs. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/downloads/covid-19-section-6008-faqs.pdf.

3Medicaid (April 13, 2020). Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), Public Law No. 116-127, Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, Public Law No. 116-136: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs). Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/downloads/covid-19-section-6008-CARESfaqs.pdf.

4Federal Register (November 6, 2020). Additional Policy and Regulatory Revisions in Response to the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency. Interim Final Rule With Request for Comments. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2020-11-06/pdf/2020-24332.pdf.

5The IFC also contains multiple provisions related to programs other than Medicaid; they are not discussed in this paper.

6Federal Register (November 6, 2020), op cit., pp. 72-73.

8Families First Coronavirus Response Act: Public Law 116-127 (March 18, 2020). Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.congress.gov/116/plaws/publ127/PLAW-116publ127.pdf.

10Medicaid (April 13, 2020). Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), op cit.

11Federal Register (November 6, 2020), op cit., p. 71.

18CMS SHO #14-002, Minimum Essential Coverage (November 7, 2014).

19Federal Register (November 6, 2020), op cit., 26 CFR 1.5000A-2.

28CMS.gov. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Monitoring-Programs/Improper-Payment-Measurement-Programs/PERM.

33Note that most states offer MEC coverage to postpartum women; however, this remains a possible scenario for non-expansion states.

34Federal Register (November 6, 2020), op cit., pp. 89-90.

35For institutionalized individuals.

3642 C.F.R. 435.725, Post-Eligibility Treatment of Income (PETI), determines the amount of a beneficiary’s income allocated to the institution to reduce the financial obligation of the state Medicaid program.