The American Health Care Act

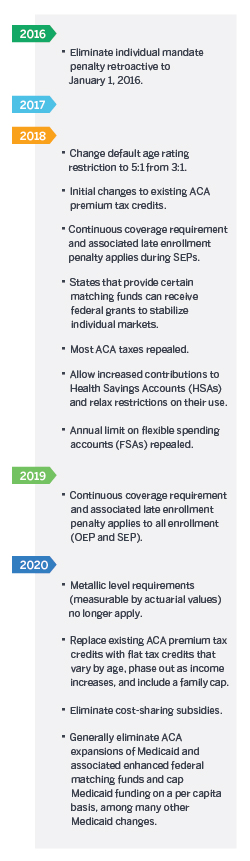

On March 6, 2017, two bills, collectively titled the American Health Care Act (AHCA), were introduced in the House of Representatives, and would repeal many key features of the ACA. The timeline in Figure 1 highlights changes under the AHCA that are most relevant to the commercial individual and small group markets from an actuarial perspective. It does not list all changes in the proposed bills.

If enacted, the AHCA would implement various commercial market changes at different times, ranging from retroactive changes to 2016 penalties to changes that take effect in 2020. Effectively, 2018 and 2019 would become “transitional” years where the rules are in flux. This would present challenges to insurers trying to price and manage their portfolios during this time period.

The legislative text of the ACA was implemented by thousands of pages of detailed regulations. The ultimate impact of many of the provisions of the AHCA repeal and replace legislation will likely depend in key ways on exactly how ACA regulations are modified in order to implement those changes. Promulgating these key changes to federal regulations will be a major undertaking should the law pass, and implementing them in time for insurers to take them into account when setting premium rates will likely prove even more challenging.

Figure 1: American Health Care Act: Timeline of key changes impacting commercial markets

It may seem like the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is fading fast under the new presidential administration and Congress, but the specifics on if, when, and how it will be replaced have yet to be finalized. New proposals from lawmakers and federal regulators shed some light on what’s to come, but so far nothing is set in stone.

In the meantime, deadlines for insurers to file premium rates for the 2018 benefit year are right around the corner1 and it seems more and more likely that the ultimate replacement to the ACA will not be able to be implemented until 2019 or 2020 at the earliest. Draft legislation2 under consideration in Congress would implement various changes with most occurring between now and 2020. The stability of the individual and small group health insurance markets during this period of transition will depend not only on the regulatory changes that are made in the interim, but also on the transparency of those changes and the further changes that will form any permanent replacement.

This paper presents five key considerations for promoting market stability for the 2018 and 2019 benefit years under the assumption that they are transitional years where many current ACA rules remain in effect. For the purpose of this paper, market stability is defined as the creation of a marketplace that both insurers and insureds will find worth participating in. This involves striking a balance between protecting insurers from the risks inherent in a market that is in transition and ensuring that consumers have access to meaningful and affordable coverage. Our definition is similar to that used by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in its recent report3 on the potential impact of the current draft legislation working its way through Congress. The CBO defines stability as “having insurers participating in most areas of the country and on the likelihood of premiums’ not rising in an unsustainable spiral.”

We provide an actuarial perspective on how certain policy changes could affect premium rates and market participation over the short term. The stability of these markets over the longer term will involve a constellation of larger issues outside the scope of this paper. Our approach is in contrast to the CBO’s perspective, which is more focused on the longer term. We note that even if a market has the potential to stabilize over the longer term under a particular set of policies, managing the transition to the new market rules in a way that minimizes short-term instability is no easy task.

Many policy changes have already been proposed by federal regulators in proposed rules or guidance and by Congress in draft legislation. It remains to be seen what changes will be finalized, both at the federal and state level, and when insurers will know the final rules they must abide by for 2018.

The five key considerations in achieving market stability are the following:

1. Don’t collapse the stool.

One of the primary goals of the ACA was to ensure that all Americans are covered by health insurance. Among many, there were three key policies designed to support that goal:

1. Guaranteed issue. This provision eliminates preexisting condition exclusions and requires insurers to enroll all individuals who request a plan during an open enrollment period (OEP) or special enrollment period (SEP). Without this provision, individuals with preexisting conditions could be denied coverage or charged rates that were unaffordable.

2. Subsidies. The ACA offers advanced premium tax credits (APTCs) and cost-sharing reduction (CSR) subsidies to low-income individuals who purchase coverage through an exchange in the individual market. These subsidies are intended to make coverage available to individuals who otherwise wouldn’t be able to afford it.

3. Individual mandate. The individual mandate is a requirement that all nonexempt citizens purchase minimum essential health insurance coverage. Failure to do so is punishable by a tax penalty. This provision is intended to encourage broad participation in the risk pool by both healthy and unhealthy individuals.

These three policies are often referred to as “legs” of a three-legged stool. All three legs are equally important in maintaining balance, and removing or altering one of them could disrupt the effectiveness4 of them all. The table in Figure 2 describes what might happen to premium rates if these policies are altered.

Figure 2: Alterations and premium rates

| Policy proposals | Potential impact on market stability |

| Removing the individual mandate | |

|

|

|

|

| Removing guaranteed issue | |

|

|

|

|

| Removing subsidies | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

These policies may or may not be part of a final longer-term replacement plan, but removing or altering one policy without considering its effect on the others and on the market as a whole could lead to an extremely unstable market in the short term.

2. Extend risk mitigation programs.

The three risk mitigation programs under the ACA—risk adjustment, reinsurance, and risk corridors—are intended to protect insurers from the new risks they face in a guaranteed issue environment. While reinsurance and risk corridors were temporary programs that expired at the end of 2016, risk adjustment was designed to be a permanent program so long as the ACA is in place.

Reinsurance

The reinsurance program was intended to protect individual market insurers from the risk of enrolling high-cost members in the first three years of the ACA, which was in turn intended to stabilize premiums. The program effectively subsidized the individual market by collecting contributions from all commercial group and individual market insurers and paying benefits to individual market insurers that enrolled high-cost members. Beginning in 2017, the reinsurance program is no longer in place, so individual market insurers needed to consider the added risk of high-cost members when setting premium rates for 2017.

Reinsurance contributions were collected for the 2016 plan year, but benefits have not yet been paid. Because 2016 premium rates were set assuming reinsurance benefits would be funded, paying out those benefits will help to promote stability.

Some states are exploring extending reinsurance-type programs through waiver programs to promote stability in the individual market in future years.7 Reinsurance is probably the single program that did the most to measurably reduce premiums in the individual market during the initial years of guaranteed issue, so it is certainly worth a look for regulators looking to promote rate stability. Another policy option under consideration would be to set up separate high risk pools for individuals with high costs or chronic conditions, similar to those in place in many states prior to the ACA (or to the ACA’s temporary pre-existing condition program [PCIP] high risk pools). However, while high risk pools can promote stability of premium rates for the remaining individual market, they are not without their own challenges8—the main one from an actuarial perspective being securing a stable and sufficient funding mechanism for the high claim costs associated with high risk pool enrollees.

The AHCA introduces the Patient and State Stability Fund providing substantial funding to states that can be used for reinsurance programs, high risk pools, and other mechanisms that could act to help stabilize premium rates in the individual market from 2018 to 2026. States can submit a plan for these funds or default to a reinsurance program. Beginning in 2020, states must provide certain levels of matching funds in order to participate, which could prove difficult for some states to muster.

Risk adjustment

The risk adjustment program is intended to redistribute a portion of premium revenue from insurers that enroll a disproportionate share of healthy, lower-cost members to insurers that enroll a disproportionate share of unhealthy, higher-cost members. Risk adjustment transfer payments are determined using a complex formula that measures the difference between the risk an insurer enrolls (measured by member risk scores) and the risk that the insurer is allowed to rate for (measured by allowable rating variables such as age and plan level). It is a permanent program under the ACA, and many insurers have invested a significant amount of resources in risk adjustment capabilities and efforts to improve risk adjustment outcomes. The federal government has also invested substantial resources in designing and administering the program, including a recent major effort to design and implement changes to the program intended to increase its accuracy for the 2017 and 2018 plan years.

Removing the risk adjustment program entirely could lead to volatile financial results and unstable market premiums unless congruent changes are made to the ACA’s guaranteed issue provisions that allow insurers to control for the health status of the members they enroll in some other way. And even if those changes were made, it is unlikely that insurers would be allowed to discontinue coverage for existing members, so insurers with an uneven share of the risk pool might still experience problems or need to consider exiting the market. (There are also implications associated with modifying the guaranteed issue provision without careful consideration, as discussed under item #2 above.) In addition, eliminating risk adjustment would give insurers an incentive to work to attract healthier risks and avoid unhealthy risks, for example by designing plans, networks, and formularies accordingly.

Each change to the risk adjustment model structure introduces additional uncertainty as insurers must estimate the impact of such changes in their scores relative to the market. However, the changes currently proposed for the model for the 2017 and 2018 plan years are intended to substantially improve its predictive accuracy. Regulators will need to balance the competing priorities and determine which has a greater chance of promoting stability in 2018—forgoing additional model changes to offer insurers a more stable set of rules, or forging ahead with changes intended to create a more accurate program. A key challenge that insurers face under the current program is in estimating the market level risk when setting their premium rates and developing their budgets and financial statements. Regulators could promote stability by continuing to work to provide insurers with interim results earlier that may help inform those projections.

The most important way to promote stability is to ensure that insurers know the rules that will apply before they set their premium rates, and for the government to commit to making the transfers for the 2018 plan year in 2019 even if the ACA is being repealed and replaced. It is crucial that insurers be able to rely on transfers actually occurring for years in which they assumed they would when setting premium rates.

The AHCA would leave the risk adjustment program in place, although much of the structure of the program could be changed or discontinued through regulation after the law is enacted.

Risk corridors

Perhaps the most controversial risk mitigation program, the risk corridor program, was intended to protect insurers against deviations of actual results from pricing assumptions in the first three years of the ACA. The federal government would share gains with individual and small group market insurers that priced their exchange plans too high and share losses with insurers that priced their exchange plans too low.9 Such risk corridor programs are common when insurers face considerable uncertainty during a significant change in market structure—for example, they were used in the rollout of the Medicare Part D prescription drug program and have been used at times when managed Medicaid programs are implemented.

The problem is that there were far more losses than gains, so the net amount owed by the federal government to the insurers significantly outstripped the amount the insurers paid in. While the program wasn’t originally designed to net to zero, congressional action restricted it to be so.10 As a result, a significant number of insurers experienced severe losses and were forced to either increase premium rates significantly, exit the market, or, in some cases, go out of business. A recent Milliman study11 found that, in aggregate, risk corridor shortfalls amounted to approximately 4% and 7.5% of earned premium for the individual health insurer industry in 2014 and 2015, respectively, contributing significantly to overall losses.

Not surprisingly, several insurers have since sued the government for their missing payments. So far, court rulings have been mixed—some on the side of the government and others on the side of the insurers. However, even if the insurers win their cases on appeal, Congress could theoretically pass a law blocking payment (by altering the standing appropriation to the federal Judgement Fund to prohibit payment of risk corridor amounts).

Although reviving the risk corridor program isn’t likely to be part of any replacement plan, paying insurers amounts owed under the program’s original design could help to stabilize the market in the interim period. It could potentially save insurers facing insolvency (and therefore save coverage for their members and promote market choices for all consumers), and stabilize premium rates among insurers that need to rebuild their capital to meet levels required by regulators after sustaining losses.

3. Extending the transitional policy.

The transitional policy, also known as the “if you like your plan, you can keep it” policy, allows individual and small group market insurers to renew existing members in plans that are not fully compliant with the ACA’s provisions. Until recently, this policy was set to expire in 2018 and remaining members still enrolled in transitional plans would have been required to enroll in an ACA-compliant plan, seek alternative minimum essential coverage, or choose to remain uninsured and potentially pay a penalty on their tax returns.

In new guidance released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on February 23,12 the transitional policy was extended through December 31, 2018. It remains true that individuals or groups enrolled in transitional plans must renew the same policy continually in order to keep it. States may also choose to end the transitional policy sooner.

Some states never adopted the policy in the first place (Minnesota and New York, for example), so those states are not affected by this new guidance. However, in states that did adopt the policy, individuals enrolled in transitional plans must choose whether to keep their plan or switch to an ACA plan13—in effect, they’re given the option to select the plan that best meets their needs. As a result, the previously underwritten (transitional) population has generally remained healthier than its guaranteed issue (ACA) successor, and the premium rates follow suit.

So while the expiration of transitional plans could have improved the average health status of the ACA risk pool and in general placed downward pressure on ACA premium rates, individuals leaving a transitional plan were likely to see sizable premium increases. Healthier individuals might have contemplated whether to remain enrolled at all.

Whenever the transitional policy expires in a state (for example, if a state chose not to adopt the new extension available for 2018), insurers will need to adjust premium rates to reflect the impact of the merging markets. Predicting the evolving risk profile and composition of an insurer’s own population under such a market disruption is challenging in and of itself. To complicate matters further, insurers will also need to consider the impact of potential changes in the average morbidity level of their populations relative to the market average—and, in particular, quantify the interactions that exist between morbidity, claim levels, and risk adjustment.

In the midst of all of this uncertainty, allowing transitional plans to continue during the interim period is likely to result in more predictable market risks and thus more stable premium rates in the individual and small group markets in 2018. Also, if ultimate market rules under an ACA replacement are likely to be similar to the pre-ACA rules that already apply to the transitional population, it may not make sense to subject that population to ACA rules for an interim year or two only to shift them right back again.

4. Consider interim rule changes carefully.

The rule proposed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS)14, a document from an internal meeting held by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB)15 to discuss the impact of that proposal, and the AHCA both outline several potential administrative and legislative actions to repeal and replace, or otherwise fundamentally change the health insurance market over the near and longer term. Among the changes proposed, the following items (not already covered earlier in this paper) in particular have the potential to affect individual and small group market premium rates in 2018.

- Individuals who do not enroll during an OEP who later have a significant life event or other qualifying circumstance during the year are eligible for an SEP under the ACA. The market stabilization proposed rule makes the qualification requirements and vetting process for individuals applying for a SEP stricter and makes it harder for insureds to change plan levels during the year (for instance, to purchase a plan with lower cost sharing than they originally selected). The rule also proposes shortening the 2018 regular open enrollment period.

- Each plan offered in the ACA market must fall into one of four metallic tiers (platinum, gold, silver, or bronze). The benefit levels for these tiers are prescribed based on the plan’s actuarial value (AV) or the expected claim liability for the plan relative to the total claim liability incurred by the member. The current nominal actuarial values are 90%, 80%, 70%, and 60% for platinum, gold, silver, and bronze, respectively, and plans are currently allowed to deviate from these nominal values by a de minimis range of ±2%. The proposed rule would allow plans to deviate below the nominal AV by 4% or above the nominal AV by 2%. (An earlier rule would already have allowed bronze plans to have an AV of up to 65% in certain circumstances.) The American Health Care Act would eliminate AV and metal level requirements altogether beginning in 2020.

- Current grace periods allow insureds receiving subsidies to continue coverage for a period of three months without paying premiums. After three months, the insurer is allowed to discontinue coverage if payment is not made and is liable for paying claims incurred in the first month. The insured can then reenroll in coverage under the guaranteed issue provision (described above) without having to pay premiums owed in the prior year. There was concern that this grace period might be subject to gaming by insureds.16 Under the market stabilization rule, the insurer can use new premium for a member to pay outstanding premium debt. However, individuals who have outstanding debt with one insurer would be allowed to enroll with another insurer, if one is available, to avoid repaying that debt.

- The federal age curve is currently restricted so that premium rates for the oldest adults cannot be more than three times higher than premium rates for the youngest adults enrolled in the same plan in the same rating region. The AHCA expands the premium range so that the highest adult rates can be five times higher than the lowest adult rates. This is consistent with plans outlined in the document from the OMB.17

- The AHCA repeals the Health Insurer Tax (HIT) and various other ACA taxes imposed on insurers and passed on to enrollees through premium.

The table in Figure 3 provides considerations for how these administrative and legislative actions might affect premium rates for 2018 if finalized.

Figure 3: Impact of administrative and legislative actions

| Proposed provision | Potential impact on 2018 premiums |

| Strengthening the qualification requirements and vetting process for special enrollment periods and shortening the regular open enrollment period |

|

| Expanding the AV metallic level de minimis ranges |

|

| Removing AV and metal level requirements entirely. |

|

| Grace period changes |

|

| Change the age rating band from 3:1 to 5:1 |

|

| Repealing the HIT and other ACA taxes |

|

In general, changing the rules in a piecemeal fashion often has uncertain consequences and risks. While these changes are mostly modest in nature compared with other changes that have been discussed, many of them do introduce some downward pressure on premium rates and so may help promote stability in the near term.

5. Transparency is key.

Successful insurers are constantly trying to position themselves for the future. Clearly articulating new reforms in a timely fashion will help insurers chart a smooth course as we set sail to the post-ACA environment, whatever that might be.

In order to promote a stable marketplace in the meantime, it is important that interim rule changes affecting 2018 premium rates are clearly communicated in time to be accounted for in 2018 premium rate development. That window is rapidly closing as insurers must generally file plans and rates for 2018 with regulators in the spring or early summer of 2017. It also means avoiding major rule changes after rates are set, which has already happened more than once to ACA insurers in the past few years.

Going forward, the same is true of any ultimate replacement rules. Regulators and legislators would do well to consider the transition from the current marketplace carefully and communicate their plans for transition well in advance of annual rate and plan filing deadlines so that insurers can plan accordingly.

Conclusion

The individual and small group markets have not yet reached any sort of equilibrium after the major changes to market rules that occurred in 2014. Moreover, the markets remain fragmented with pools of insureds in grandfathered or transitional plans rated separately from the reformed “single” risk pools subject to the ACA. Given the relatively small size of the individual and small group markets to begin with, bringing these fragmented pools back together may be necessary to create stable markets in the longer term. However, even if policymakers reach consensus on how to glue the fragments back together, it remains to be seen if they will also implement that consensus plan in a way that enables insurers (and their actuaries) to have a hope of predicting the risks they are being asked to undertake.

In the meantime, it is critical that policymakers take steps to maintain a stable market in any interim years, including 2018, and to lay out a transparent and orderly transition from current rules to the future rules that will apply in the long run. Ultimately, insurers will only participate in a market where they have enough information to accurately price their products and where market rules strike a balance that ensures a sustainable and large enough risk pool.

1CMS (February 17, 2017). DRAFT Bulletin: Revised Timing of Submission and Posting of Rate Filing Justifications for the 2017 Filing Year for Single Risk Pool Coverage; Revised Timing of Submission for Qualified Health Plan Certification Application. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Regulations-and-Guidance/Downloads/Revised-2017-filing-timeline-bulletin-2-17-17.pdf

2House of Representatives. (March 6, 2017). Budget Reconciliation Relating to Remuneration from Certain Insurers. Retrieved from https://waysandmeans.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/AmericanHealthCareAct_WM.pdf and House of Representatives (March 6, 2017). Budget Reconciliation Legislative Recommendations Relating to Repeal and Replace of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Retrieved from http://energycommerce.house.gov/

sites/republicans.energycommerce.house.gov/files/documents/AmericanHealthCareAct.pdf

3Congressional Budget Office (March 13, 2017). American Health Care Act- Budget Reconciliation Recommendations of the House Committees on Ways and Means and Energy and Commerce. Retrieved from https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/americanhealthcareact.pdf

4For an interesting case study of what happened when the stool was collapsed in Brazil’s health insurance market, see: Rezende Furtado de Mendonça, D. and van der Heijde, M. (June 15, 2012). Lessons from Brazil: Regulatory changes in the health insurance market. Retrieved March 17, 2017, from http://us.milliman.com/insight/health/Lessons-from-Brazil-Regulatory-changes-in-the-health-insurance-market/

5IRS.gov (February 15, 2017). Individual Shared Responsibility Provision. Retrieved from https://www.irs.gov/affordable-care-act/individuals-and-families/individual-shared-responsibility-provision

6Houchens, P. & Fohl, Z. (February 6, 2017). Cost-sharing reduction plan payments under the ACA: Summary of health insurer cost-sharing reduction payments in CY 2014 and CY 2015. Association for Community Affiliated Health Plans. Retrieved February 27, 2017, from http://www.communityplans.net/research/csr/

7For example, Alaska and Minnesota:

Jost, T. (June 16, 2016). Alaska reinsurance plan could be model for ACA reform, plus other ACA developments. Health Affairs Blog. Retrieved February 27, 2017, from http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/06/16/alaska-reinsurance-plan-could-be-model-for-aca-reform-plus-other-aca-developments/

Montgomery, D. (January 19, 2017). Minnesota lawmakers hope ‘reinsurance’ will help fix health insurance market. Here’s how it would work. Twin Cities Pioneer Press. Retrieved February 27, 2017, from http://www.twincities.com/2017/01/19/minnesota-lawmakers-hope-reinsurance-will-help-fix-health-insurance-market-heres-how-it-would-work/

8Lambrew, J. and Montz, E. (February 28, 2017). States Be Warned: High-Risk Pools Offer Little Help At A High Cost. Health Affairs Blog. Retrieved March 17, 2017, from http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2017/02/28/states-be-warned-high-risk-pools-offer-little-help-at-a-high-cost/

9Norris, van der Heijde, & Leida (October 2013). Risk Corridors Under the Affordable Care Act – A Bridge Over Troubled Waters but the Devil’s in the Details, pp.1, 5-10. SOA Health Watch. Retrieved March 17, 2017, from http://www.milliman.com/insight/2013/Risk-corridors-under-the-ACA/

10Norris, D., Perlman, D., & Leida, H.K. (December 2014). Risk Corridors Episode IV: No New Hope. Milliman Healthcare Reform Briefing Paper. Retrieved February 27, 2017, from /-/media/Milliman/importedfiles/uploadedFiles/insight/2014/risk-corridors-no-new-hope.ashx

11 Houchens, P., Clarkson, J., Herbold, J., & Fohl, Z. (March 2017). 2015 commercial health insurance: Overview of financial results. Retrieved March 20, 2017, from /-/media/Milliman/importedfiles/uploadedFiles/insight/2017/2015-commercial-health-insurance.ashx

12CMS (February 23, 2017). Insurance Standards Bulletin Series -- INFORMATION – Extension of Transitional Policy through Calendar Year 2018. Extended Transition to Affordable Care Act-Compliant Policies. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/cciio/resources/regulations-and-guidance/downloads/extension-transitional-policy-cy2018.pdf

13AHIP (April 12, 2016). State Responses to Administration Policy on Individual and Small Group Coverage Extensions. Retrieved February 27, 2017, from https://www.ahip.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/MAP-Transitional-Plans.pdf

14HHS (February 17, 2017). 45 CFR Parts 147, 155, and 156 CMS-9929-P RIN 0938-AT14: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Market Stabilization. Federal Register. Retrieved from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/02/17/2017-03027/patient-protection-and-affordable-care-act-market-stabilization

15OMB (January 31, 2017). Immediate 2017 Actions to Stabilize the Private Health Insurance Market. Retrieved from https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eoDownloadDocument?pubId=&eodoc=true&documentID=2650

16Kolber, M. & Leida, H. (November 17, 2014). How consumers might game the 90-day grace period and what can be done about it. Health Affairs Blog. Retrieved February 27, 2017, from http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/11/17/how-consumers-might-game-the-90-day-grace-period-and-what-can-be-done-about-it/