Even at this early stage, we see that countries that attacked the COVID-19 pandemic early and aggressively now appear to be showing the most signs of success in controlling it, in managing their medical resources and in minimising deaths and infections. Two approaches we have seen are contain and delay.

Contain

The contain strategy is a rigorous use of non-pharmaceutical measures to isolate all confirmed cases, suspected cases and close contacts with either confirmed or suspected cases to contain the transmission of the virus and avoid further spread. Contain has been the approach taken in China and South Korea. In China, the outbreak of COVID-19 began taking on serious proportions in Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei province, in mid-January. Around that time, the Chinese government imposed travel restrictions, including locking down all of Wuhan on 23 January, and other strict social distancing and quarantining measures. Testing and treatment were also aggressively ramped up. By 28 January, more than 6,000 doctors and nurses had flown into Hubei province from different Chinese cities, and that number quickly increased to around 30,000 by mid-February. Overall, over 42,000 doctors and nurses from 29 provinces or autonomous regions and municipalities came to help people in Hubei. Medical supplies were also pooled into Wuhan and Hubei province from all over China and even around the world.

Among other things, these steps bought China time to work on building up its medical resources, such as hospital bed availability, ventilators for patients and protective wear for healthcare workers. The contain measures may have seemed drastic at the time, but early results indicated they were effective. By 10 March, healthcare delivery system capacity had improved enough in Hubei province that all makeshift hospitals could be closed (at least on a temporary basis) due to capacity redundancy. On 7 April, China reported no new cases in a day for the first time since the outbreak began.1

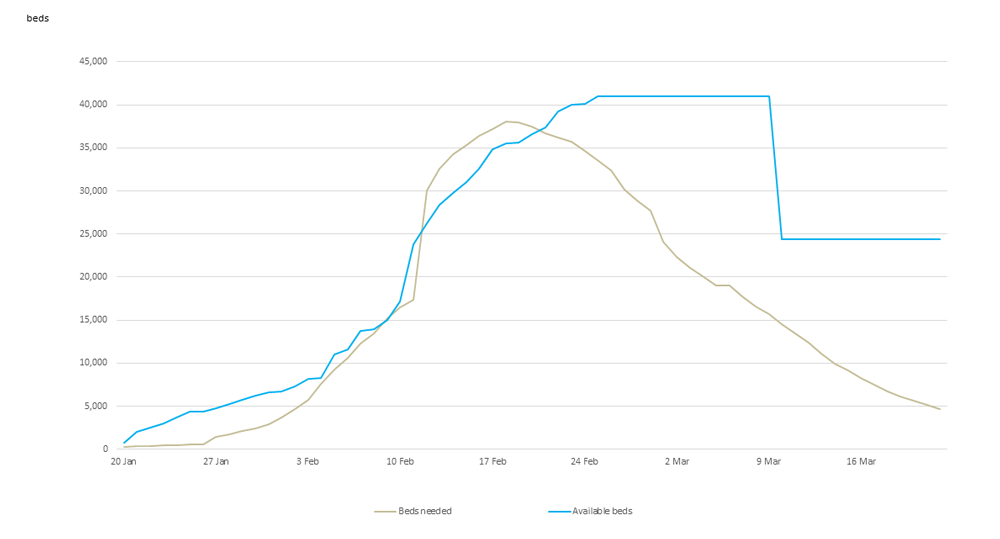

Figure 1 shows hospital bed capacity versus the number of patients in Wuhan over time. We only show the data between 20 January and 22 March, when the data exhibits the most significant patterns that are discussed in this study. Please note that the results shown here are entirely dependent on the figures published publically.

Figure 1: Hospital beds needed vs. beds available in Wuhan2

As shown in Figure 1, there was a significant jump in the number of beds needed as more than 13,000 cases were confirmed on 12 February. The driver of this increase is not entirely clear, but may be due to more aggressive testing and changes in local reporting. It is also important to note that the deficit between beds needed and bed availability (capacity deficiency) could be underreported early on. Based on local news reports, this capacity issue likely already existed3 but was not explicitly reflected in the reporting of confirmed cases, or hospital beds needed, until 12 February. Locals in Wuhan also believe the capacity deficiency was getting worse from late January to early February,4 when it was finally reflected in the reported numbers.

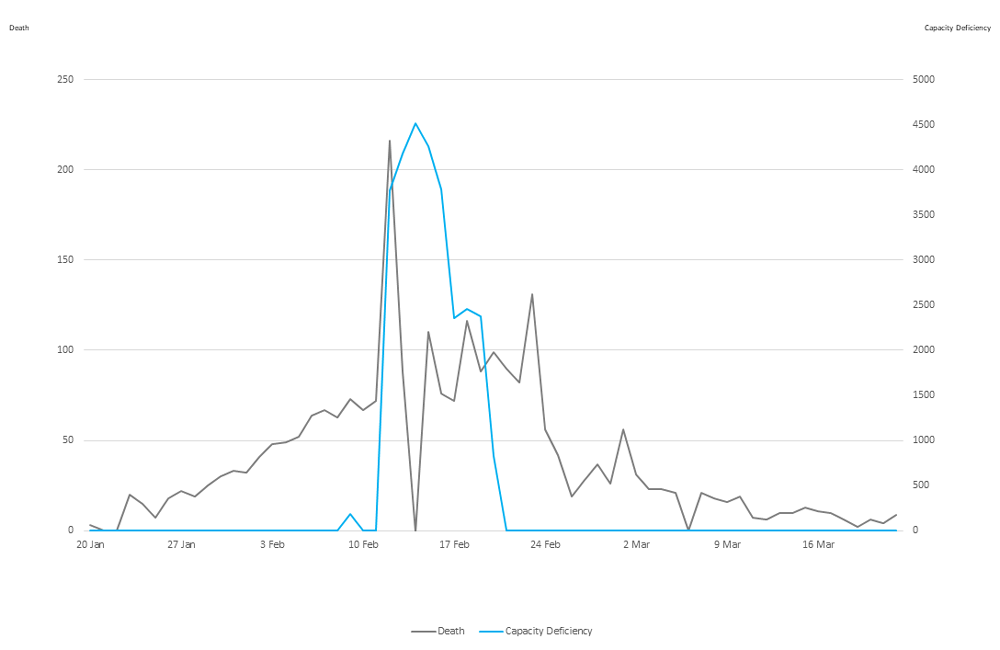

Figure 2 shows the deaths as compared to the hospital capacity deficiency as we believe there is strong correlation between the two series. There is a clear spike in both deaths and the capacity deficiency around mid-February.

Figure 2: Wuhan COVID-19 death cases vs. capacity deficiency 5

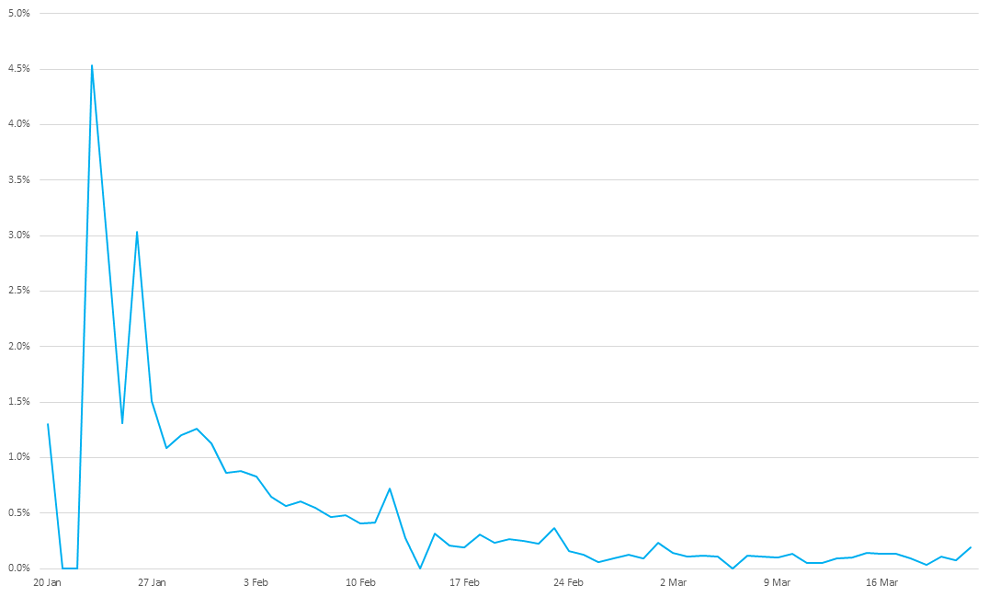

Figure 3 illustrates the change of the ratio of deaths to remaining confirmed cases of infection over time. It was much higher in late January when the capacity deficiency was significant and then quickly reduced, staying under 1% since February and dropping afterwards. While different treatments were explored over time and the effectiveness of treatments improved, limited delivery system capacity in the early stage could be another significant contributing factor to the higher death rate early on.

Figure 3: Deaths as a percentage of remaining confirmed cases in China 6

Delay

Rather than completely stopping transmission of the virus under the contain strategy, a less aggressive delay strategy is to slow down the transmission of viruses so that more medical capacity can be put in place before the outbreak, also hoping that vaccine or other medical treatment could be found during this delay period. As opposed to the contain strategy, the delay strategy was adopted by Singapore and Hong Kong. This strategy prioritises medical needs so that existing medical capacity will be preserved for those with serious conditions. It appears to be working well in Singapore and Hong Kong. It should be noted, however, that both Singapore and Hong Kong have much warmer climates than Wuhan. Viruses tend to have more difficulty surviving and spreading in warmer climates. Whether this is applicable to COVID-19 remains a point of debate. There is also a chance that the virus could move back and forth between the northern and southern halves of the globe as the seasons change.

Similar delay strategies could be taken by other countries, possibly called by other names. For example, France favours a proportional and progressive strategy to handle the pandemic and hopes to avoid drastic measures as long as possible.7 And different states in the US may have different strategies or different strategies at different times.

Moving forward

The virus has spread to over 170 countries worldwide at a time when the world is more connected than at any time in human history. It is clearly beneficial to work together and to learn from the experiences of others in dealing with this outbreak worldwide as some of the challenges are the same regardless of the strategies taken by individual countries.

In the absence of a cure or vaccine for COVID-19, capacity deficiency in this outbreak has been strongly correlated with death rates. We have seen high death ratios as a percentage of confirmed cases in Hubei province in China as well as in Spain and Italy.

One interesting example of learning from past experience is found in the use of makeshift hospitals. As with the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, makeshift hospitals have proven to be extremely helpful for expanding medical system capacity quickly. In Wuhan, use of temporary hospitals enabled all those with confirmed infections to be admitted to avoid transmission, regardless of the severities, and to provide focused treatment. This could be different from other regions where only those infected with severe symptoms are admitted into hospitals. On 24 March, the National Health Service (NHS) of the UK announced it would build a makeshift hospital of 4,000 beds in London.8 Similarly, in the US, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that the state of New York would establish temporary hospitals at four locations, including two convention centers and two large university athletics facilities. Outside New York, which has been among the hardest-hit areas of the US, other universities, including Yale, are building makeshift hospitals in their gyms, too. And up to 3000 hospital beds will be completed in McCormick Place Convention Center in Chicago.9

Regardless of whether it is Wuhan, Italy or New York City, public health systems and governments face many similar challenges when battling this worldwide pandemic, including:

- Identifying hotspots before they turn into local epidemics and keeping the public informed

- Getting information for decision making, making informed decisions and then taking action.

- Deploying limited medical resources to meet immediate needs while reserving capacity for day-to-day medical needs.

- Collecting and sharing lessons learned from across the public health systems

- Mitigating the impact of pandemics on key industries, international trade, international supply chains, etc.

- Accessing community-based services in case of lockdown or shelter-in-place requirements

- Mitigation strategies including private insurance, which is used not only to reimburse medical expenses, but also to protect against other events such as business interruption or even the cancellation of major sporting events such as the Olympics

While there are many similarities across the world, local strategies differ. For example, China and other Asian countries learned from SARS and moved quickly, while Europe and North America were not affected much by SARS and didn’t take the same quick actions. A proven success in one region may not necessarily lend itself to others. It also may not make sense to compare across countries because of the rapidly developing nature of this pandemic. China did not have much information about COVID-19 when it began responding in January. Government officials did not know the death rate, the incubation period or potential treatment strategies. As we learn more, those lessons are useful information for other countries implementing strategies to address COVID-19.

It is really too early to know which strategy is better—contain or delay—or whether an even better strategy has yet to emerge. The lens through which one evaluates the question also matters. From a pure public health perspective, there is a strong case for contain. From an economic perspective, however, strict contain measures can be devastating. One approach may work better in one particular country than another, and the conclusions may be different from a population health perspective as well as from an overall economic perspective. One thing that is clear, however, is that we are all learning about COVID-19 as we go.

1Hernandez, J.C. (7 April 2020). China hits a coronavirus milestone: No new local infections. New York Times. Retrieved 8 April 2020 from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/18/world/asia/china-coronavirus-zero-infections.html.

2Updates on COVID-19 in Wuhan. Retrieved 8 April 2020 from http://wjw.wuhan.gov.cn/.

3Zhang, C. (23 January 2020). COVID-19 Patients with Serious Conditions in Wuhan Say: Difficult to Get Admitted to Hospitals. Retrieved 26 March 2020 from http://news.ifeng.com/c/7tTLiu7tp8C.

4Sina Finance (8 February 2020). What are the difficulties faced by Wuhan bed resources? Retrieved 8 April 2020 from https://finance.sina.cn/2020-02-08/detail-iimxxste9773894.d.html/.

5Updates on COVID-19 in Wuhan, op cit.

7France 24 (7 April 2020). France's Covid pandemic has not yet peaked, says health minister. Retrieved 8 April 2020 from https://www.france24.com/en/20200407-covid-pandemic-has-not-yet-peaked-in-france-says-health-minister.

8Kelly, G. (3 April 2020). The story of NHS Nightingale: How Britain’s biggest hospital was built from scratch in under two weeks. The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 April 2020 from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/health-fitness/body/story-nhs-nightingale-britains-biggest-hospital-built-scratch/.

9Krauser, Mike. (10 April 2020). Phase 2 Complete At McCormick Place Overflow Hospital. WBBM Newsradio- Chicago. Retrieved 13 April 2020 from https://wbbm780.radio.com/articles/phase-two-complete-at-mccormick-place-overflow-hospital